Here’s a data roundup on why optimal admission pricing is especially important right now, findings to inform these conversations, and the important things to know if you’re considering a pricing study or a price change.

You’re not imagining things: There’s been increased talk and awareness about data-informed optimal admission pricing among cultural organizations since the pandemic began in 2020. Today, we’re rounding up some of the data and facts informing these discussions.

There’s a lot of research where these items come from, and we’re hoping this article will also serve as a resource for more nuanced discussions. Here, we will aim to:

This is a big topic with several links available for deeper dives and contemplation – so let’s dive right in.

Why optimal pricing is particularly important post-pandemic

We’ll start with the obvious: The height of the pandemic was a rough time for most cultural institutions. Many cultural entities shuttered their doors for periods of time and suffered financially. And while some organizations benefitted from redistribution of demand – such as zoos, parks, and gardens – others like science centers, children’s museums, and symphonies suffered from this shifting market preference and continue to do so.

Logically, cultural entities began to ask more questions about their own bedrocks of solvency and sustainability. If another global, national, or regional emergency takes place, how can organizations continue to ensure their financial futures? Three realities, in particular, seem to be prevalent:

Expenses continue to outpace revenues for cultural organizations.

Cultural organizations had a growing funding issue even before the pandemic. Let’s step back in time to 2018 when I had a more noticeable side-part (before a mass of Gen Z arrived on the scene to poke us millennials to new fashion trends) and we published this video on revenues vs. expenses for the cultural industry:

The data is explained in this article: The Increasing Costs of Running Cultural Organizations (DATA)

Though the side-part may have gone out of fashion, it is still true that expenses outpace revenues for cultural entities. Between 2010 and 2016, average per capita operating expenses increased 27.1% while per capita revenues increased by only 17.3%. This was not sustainable.

The pandemic, coupled with the escalating costs of doing business, further exacerbated this challenging condition. Today, our analysis of 13 visitor-serving organizations in the US indicates that for the most recent three-year period spanning 2021-2023, per capita operating expenses increased by 16.7% while per capita revenues increased by 5.5%.

An additional test to the long-term solvency of many organizations is the recently-observed historic low in US population growth – meaning that when contemplated on a per capita basis, there is not a large population bubble coming down the pipeline in the foreseeable future that can significantly add to the overall size of our audiences.

Obviously, a business model that features expenses significantly outpacing revenues is not sustainable. As was the case in 2018, potential solutions include diversifying revenues (including taking membership more seriously), integrating audience and market research trends into engagement strategies in order to maximize market potential, and – the point of this article – examining funding models.

Simply put, this alarming trend makes good business decisions and smart investments of time, energy, and resources all the more important. If we cannot keep our lights on, then we cannot exist, let alone create the exhibitions, programs, performances, and experiences that educate and inspire our communities. Understanding your organization’s optimal, data-informed price point – that point at which an organization is maximizing admission-related revenue without notably jeopardizing attendance – is increasingly critical for securing the funding required to not only survive, but to thrive.

Admission cost is a more stable revenue lever than attendance volume.

“Well, we just need to attract more people!” Sure, and this is a good strategy – but it’s not always a reliable one. This is especially true in our world of shifting health issues, economic concerns, crime factors, and weather-related disruptions. As we learned from the pandemic, sometimes external conditions in our macro-environment limit attendance.

Consider this easy-math example: Let’s say yours is an organization that welcomes one million visitors a year at a cost of $5 per person. You charge $5 per person because that just feels right (or is comparable to the museum down the street, and they must have a smart reason for charging that fee, right?). We’re keeping things simple in this hypothetical world wherein there are no philanthropic donations, membership options, or any other means of access, so, with a million visitors a year at $5 each, this means your entity has $5 million of annual revenue.

Now let’s say there’s a major weather event during the year that decreases attendance by 20,000 people. Your organization would then only achieve $4.9 million in revenue.

But what if you knew that you could charge $8 per person and welcome 900,000 visitors each year? You’d have annual revenues of $7.2 million dollars – $2.2 million more than if you welcomed one million people at $5. When that same weather event takes place impacting 20,000 guests, your revenue is still $7.04 million – $2.14 million more than if the museum were charging $5 and experienced the same weather event. (This example presumes, of course, that the data support a broad market tolerance for a price increase from the hypothetical $5 per person to the equally hypothetical $8 per person price point.)

The point of this simple example is that there are two primary means of increasing admission-related revenues. One is the volume of visitation, or to grow the size of your audience. The other is to optimize your admission price. In our analysis and observation, the risks associated with achieving and sustaining an increase in the volume of visitation for an organization vastly exceed the risks associated with optimizing your admission price.

And, of course, this makes sense: Unless your organization has been woefully underperforming its engagement potential – through some combination of poor communications, marketing, programming, operations, public perceptions, etc. – then you are probably already achieving a realistic volume of visitation. In other words, it’s highly unlikely that a well-run organization is going to turn over a magic engagement rock and suddenly discover 25% more visitors to walk through its door.

On the other hand, even well-run organizations confront periods of price inefficiency when it may be possible to optimize its admission prices. More to the point, price optimization is a product of a data-informed process whereas significant attendance growth generally either relies on (a) massive prevailing population growth (which is beyond the control of your organization); and/or (b) overcoming poor performance (which is not so much of an optimization as it is a correction).

Black swan events occur – more often than leaders may realize.

Major disruptors can and do happen. At IMPACTS Experience, we commonly contemplate models to predict potential attendance patterns for individual organizations. To do this, we work with our university partners – experts with access to supercomputational capacity – to run millions of simulation trials to develop a data-informed estimate of future attendance potential.

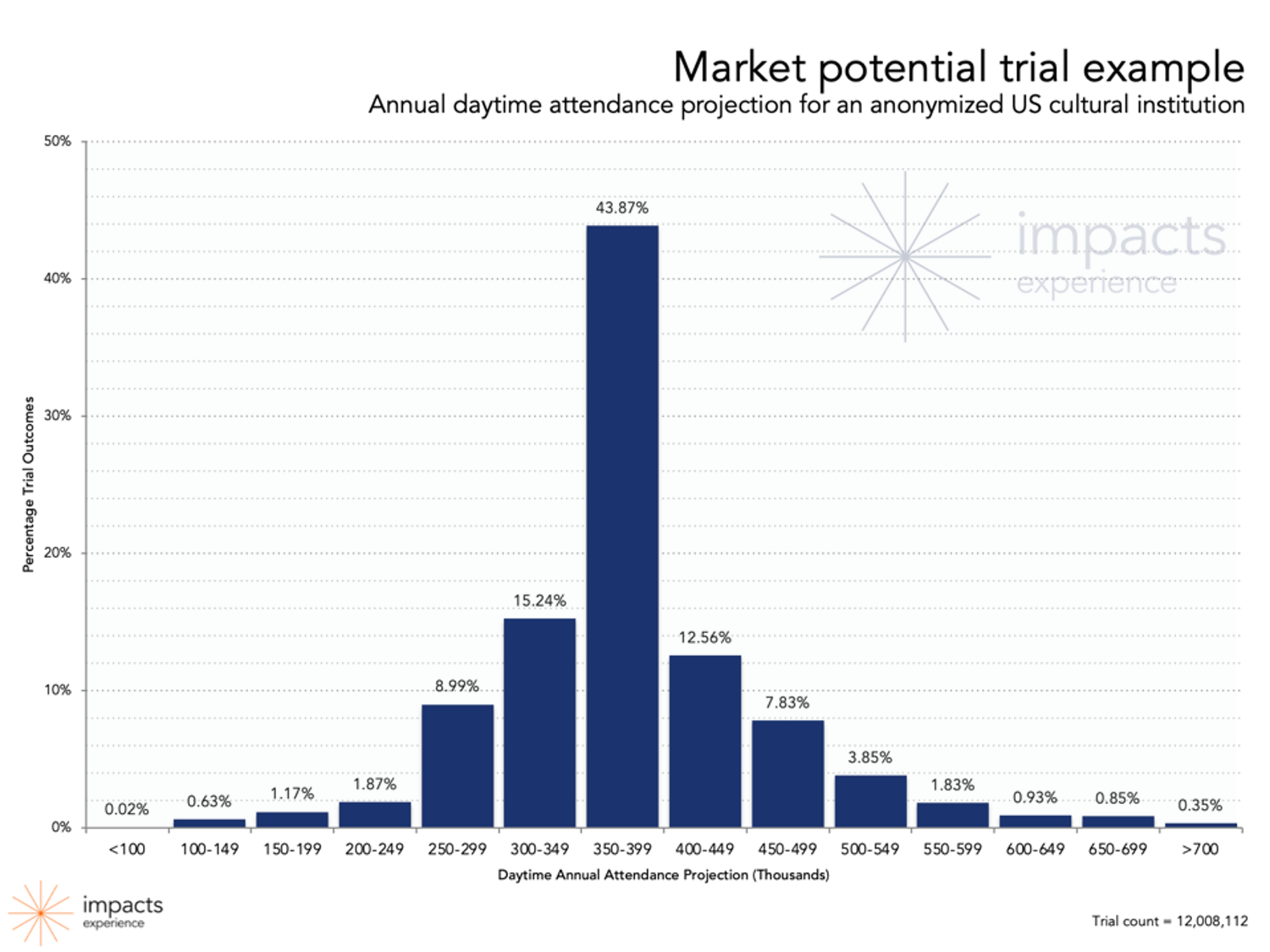

These models contemplate actuarial overlays that recognize the potentiality of various Black Swan-type risks such as major climate events (e.g., hurricanes), labor disruptions (e.g., employee strikes), civil unrest, crime, natural disasters (e.g., seismic activity), terrorism…the list goes on. In essence, they contemplate not only the likelihood of more usual factors but also the things that can and do make a bad day a bad year. Take a look at an example of the market potential projections for an anonymized US cultural organization, the product of more than 12 million trial simulations, here.

If the modeled organization did not suffer any major disruptors, then this organization could reasonably expect between 350,000–399,000 attendees. But consider this: There was nearly a 13% chance that life’s messiness would intervene, and this particular organization would welcome fewer than 300,000 attendees. And, on the optimistic upside, there was approximately a 28% expectation that the organization would welcome 400,000 or more people through its doors!

Again, read more about this analysis here: When Black Swans Happen: How Cultural Entities Can Better Respond to Disruption

The point? Black swans and disruptive events happen. Smart modeling knows they can happen. Smart leaders do as well. Thus, it’s all the more important for entities to develop more agile business models and save for a rainy day – literally.

Debunking (or at least rethinking) the most common concerns related to pricing considerations

There are several considerations related to understanding an organization’s own data-informed, optimal admission pricing and structure.

For cultural executives, it’s axiomatic: Good business practices and more revenue enable more programs, better experiences, and greater opportunities for effective mission execution. This is often born of the wisdom acquired from managing people, budgets, and programs alongside financial outcomes and actual outputs.

But sometimes things get confused, and people think that smart business practices are at odds with mission execution – and specifically with welcoming affordable access audiences.

Admission price is not an affordable access program, and being free (or discounted) is not the same as being welcoming.

Let’s talk freely about free admission. To do this, we’ll take another dive into the past and share another Fast Facts Video:

In 2019, when this video was produced, free admission museums welcomed guests with only 1.3% lower household income than did paid admission organizations – not a significant variance. As of Q2 2024, free admission museums welcomed guests with a 2.1% lower household income than did paid admission organizations. Again, this modest variance tends to affirm that free admission is hardly the panacea to engagement.

Research also shows that free admission organizations often have lower guest satisfaction rates, are less likely to be recommended to friends, and are not seen as notably more welcoming. Here’s the data. Don’t be upset with this messenger – the fact that people value what they pay for is a finding espoused by Nobel Prize-winning economists.

What’s going on here? As it turns out, the kinds of people who visit museums are… well, the kinds of people who visit museums.

Being free is not the same as being welcoming. If we want to truly engage affordable access audiences, then an investment is required to develop targeted access programs that actually reach these intended audiences – who may not already follow your museum or performing arts organization. Investments require financial backing, and now we’re back at square one: In order to effectively welcome affordable access audiences, cultural entities need money to do it. That money needs to come from somewhere, such as the high-propensity visitors willing to pay an organization’s optimal admission price.

Admission price is not a top barrier to attendance.

Make no mistake: Economic concerns – or, perhaps better said, broad perceptions concerning the economy – are heightened now as we approach the presidential election. In fact, we’ve seen “economic concerns” escalate as a barrier to participation for cultural organizations since 2021. But what are these economic concerns that potential guests are citing as reasoning to defer a visit?

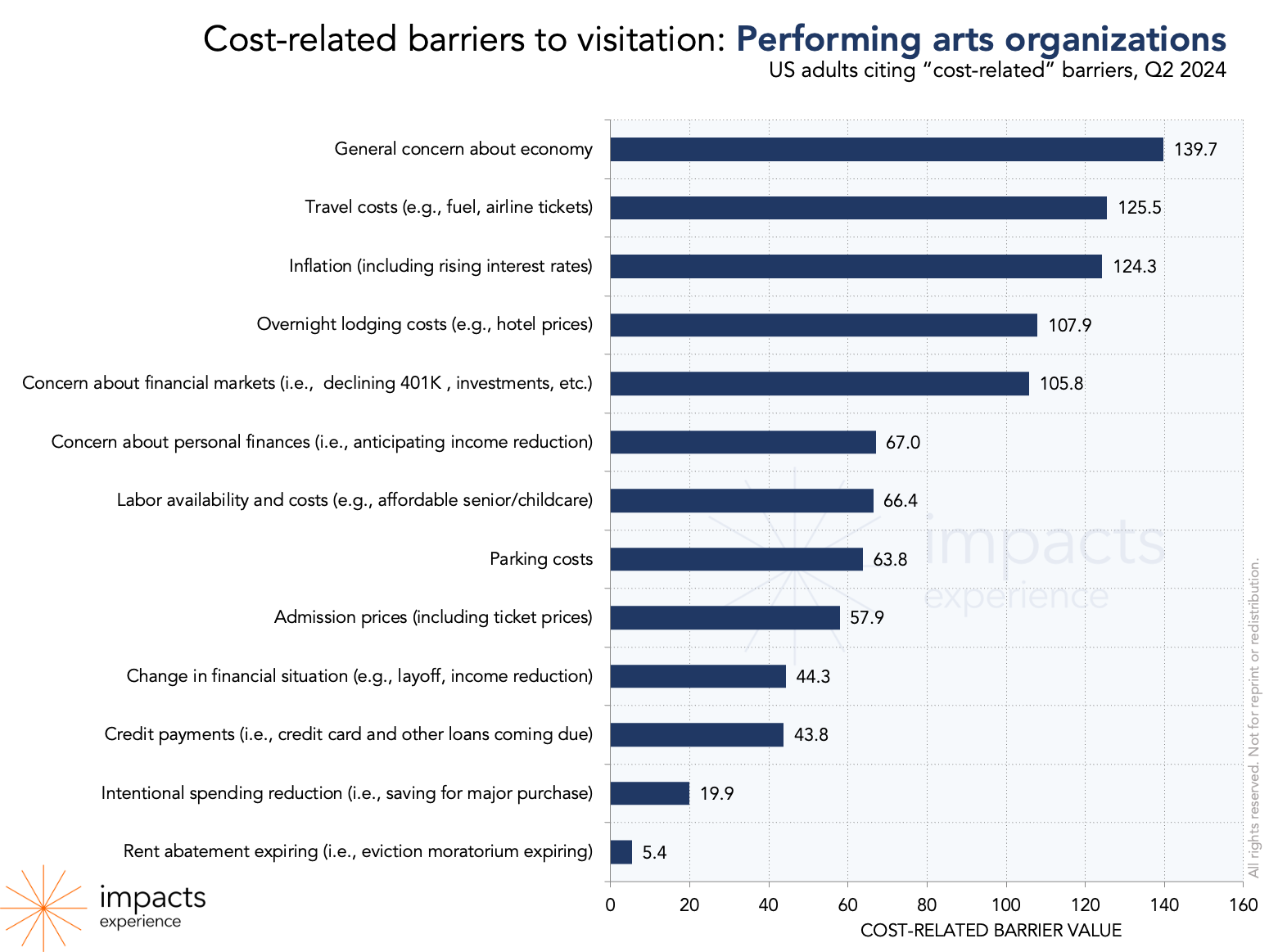

Let’s take a look at data we published at the middle of this year on this very topic. To understand these cost-related concerns, we simply ask respondents who cite cost-related barriers to specifically identify the economic and financial factors that inform their perceptions and behaviors. We rely on lexical analysis processes wherein we ask open-ended questions (thus minimizing framing and other potential biases). Responses are quantified as index values, which are a way of quantifying proportionality. For example, a factor with an index value of 100 is twice as large of an economic-related barrier to attendance than another factor with an index value of 50.

The research below contemplates exhibit-based organizations (e.g., museums, zoos, aquariums, etc.) and performing arts organizations (e.g., theaters, symphonies, ballets, etc.) separately. You’ll notice that the responses are generally similar:

For both exhibit-based and performing arts organizations, admission cost is notably less prominent on the list of potential cost-related barriers. When folks cite cost-related concerns as a reason why they are not attending a cultural organization, they are usually NOT talking about your ticket price.

Remember that when someone considers leaving their home to attend a museum or theater performance, they aren’t usually going out to do just that one thing. The museum or theater trip is often a part of a bigger day or experience. After all, folks need to get to the museum, and they often want to eat something before a performance. While it’s easy to consider our cultural experiences alone – and thus focus solely on the ticket price that we can control when cost is a mentioned barrier – this mindset risks overlooking the totality of the guest experience. Attending a cultural organization is often one part of a larger plan that includes not only considerations for the visit to the organization itself but travel and logistics requirements, food needs, and other expected expenses that enable the entire trip.

Frustratingly, we observe for both exhibit and performing arts organizations that general concern about the economy and inflation are top areas of concern. It’s frustrating because – mighty as your organization may be – you are unlikely to singlehandedly assuage fears related to the national economy. Knocking $3 off your price is not likely to make much of a difference in calming concerns about inflation, retirement savings, credit card debt, or hotel costs for individual guests…but losing that $3 per person can add up to a big financial blow for an organization.

We’ll continue to track this metric through and after the election, and we will provide an update in 2025. In the meantime, it’s worth noting that admission cost has not been observed as a top historic barrier to attendance, and even now with economic concerns heightened, admission cost is not playing a major role in a decision to attend a cultural organization.

Cultural organizations are perceived to be worthy of their admission price.

There’s additional good news: Both exhibit-based and performing arts entities are generally considered to be worthy of their admission prices. Value is considered differently than if something is expensive or not. For many organizations, their admission price can be considered both a “good value” and “expensive” simultaneously. Indeed, many of the highest ranked and most esteemed cultural organizations in the US proudly carry the common price description of “Expensive, but worth it.”

Let’s find a mirror here for some real talk: Cultural organizations tend to be staffed with very kind, very thoughtful people who passionately believe in the missions and good works of cultural organizations and find fulfillment in sharing these passions for the benefit of their communities. It is also true that many of these same good people too often underestimate the value of the experience and inspiration that they provide. Many are also guilty of thinking of themselves (or their neighbors, or their friends) as the targeted audience for many programs and develop more internal measures of what they perceive as a good value instead of taking heed and prioritizing external measures of value. What matters is the perceived quality of the experience relative to the admission cost – not the cost itself.

A Chipotle burrito costs approximately $9.50. Extra guacamole costs $2.65.

Cultural organizations provide meaningful memories and transformative experiences, and we regularly work with leaders who wonder if an increase in their admission price is worth the cost of adding a scoop of guacamole to their lunch.

You can see the data recently segmented for eleven organization types in this article: Cost and Value: Are Museum & Performing Arts Tickets Worth It? (DATA)

Considering a price change? Here’s what you need to know.

Let’s say you’re wondering if your organization should reconsider its pricing strategy or revisit its admission basis. There are several important things to keep in mind. This section just barely scratches the surface, but it provides some important baseline information and best practices.

Understand your own value-for-cost perceptions.

Not all organizations can raise their prices without negative consequence. An organization may be struggling with revenue but also already optimized its price. In this case, a change in pricing may jeopardize attendance such that the price increase will not offset an anticipated, attendant decline in attendance. Or an entity may change its price so frequently and without adequate research that it frustrates the public or deteriorates trust in the organization.

It isn’t so much that an organization itself gets to decide when to raise its price. In many ways, the market decides. An organization merely makes the decision to research its value-for-cost perceptions in order to understand pricing opportunities. Sometimes data suggest that an entity is “leaving money on the table,” and other times data suggest it is not the right time to increase pricing as doing so would have negative financial or reputational consequences.

It isn’t simply raising price that can present a risk, but also pursuing a new pricing strategy without research to indicate that the market will tolerate this change. We see this happening sometimes when organizations get carried away with dynamic pricing before research suggests that it will be accepted. Doing this too soon (or just out of a want for a “sexy” pricing strategy) can backfire because it confuses or frustrates audiences. When this happens, we see “access challenges” emerge as a barrier to attendance.

All this is to say that understanding data-informed, optimal pricing is a science, not an art. It requires research related to your own individual institution and the experiences that you offer.

Types of pricing: Static, differentiated, variable, and dynamic.

Speaking of dynamic pricing, what is it? It’s a good question – especially because some organizations say they feature dynamic pricing when they actually have variable pricing! (And that may be a good thing. We continue to observe select resistance to dynamic pricing in certain markets at this time – but we’re watching it.) We provide an overview of types of pricing here, as well as the pros and cons of these pricing strategies.

With static pricing, admission fees remain predictable and consistent day-to-day and person-to-person. Static pricing is also known as “fixed pricing.” The fee stays the same no matter the day of the week or time of day. For an organization with an adult admission fee of $20, Tuesday at 10:00am has a $20 adult admission fee, and Saturday at 1:00pm has a $20 adult admission fee. Organizations with only one price differentiator in addition to an adult admission price – usually a child admission price – are also often considered to have static pricing. Technically, having two pricing options (adult and child) could be considered differentiated pricing, but having a separate child price is such a common expectation among Americans for many out-of-home leisure activities that “fixed pricing” also applies to this practice at cultural organizations.

Differentiated pricing is a strategy by which organizations offer different prices for the same experience based on certain visitor eligibility criteria. In a nutshell, differentiated pricing can help organizations perceptually appeal to different audience segments and provide cultural organizations with more tools to respond to unique audience attributes than the “one size fits most” approach typical of static pricing.

For example, an organization that offers different price points on the same day/time for people based on if they are adults, locals, children, teachers, veterans, or seniors has a differentiated pricing strategy. Eligibility for the applicable price depends on an attribute of the visitor. This kind of pricing strategy is very commonly deployed among many exhibit-based cultural entities in the United States (e.g., museums, zoos, aquarium, gardens, and historic sites). It is somewhat less common among performing arts organizations as the price – while perhaps differentiated based on visitor attributes – tends to contemplate additional variances related to specific content or programming. Also, performing arts organizations tend to have more constraints on capacity. Popular musical performances sell out. Zoos generally do not.

A beauty of differential pricing opportunities is that the criteria are readily understood and accepted by the public. Few people begrudge a veteran, an educator, or a senior citizen receiving a unique price.

Variable pricing is a strategy in which admission price varies based on demand for the experience. Unlike differentiated pricing, which is most often based on the attributes of folks coming in the door, variable pricing is based on the demand for the visitor experience and how many folks want to come through the door at the same time. In variable pricing, adult admission to the same museum may cost $20 in February, and $40 in July. Or it may cost $12 on Tuesday, and $29 on Saturday. Performing arts organizations are no strangers to variable pricing, and it works well for many in this sector! Performances tend to be time-specific with limited capacities and differing levels of quality based upon seating.

For exhibit-based organizations, a potential benefit of variable pricing is the ability to maximize revenue on high-volume (read: high demand) days. The hope of employing this strategy is that the impacts of crowding on the guest experience will be mitigated by shifting visitation patterns to less peak periods. People paying a premium to visit during a peak period should enjoy a substantively similar experience as visitors visiting during a lower demand cycle. However, as many exhibit-based organizations have come to realize, there remains market pushback on this pricing strategy for organizations that maintain open hours with abundant access.

Dynamic pricing is an experience and revenue management tool that responds to inconstant market conditions with varying prices. Conceptually, the basic argument in favor of dynamic pricing is that fixed pricing models tend to disserve two types of would-be visitors: (a) Those who would only visit if they were able to pay less than the fixed rate, and (b) those who would be willing to pay more than the fixed rate. In a perfect world, this argument is compelling. However, our world remains imperfect, so let’s consider the practical and more pertinent benefits and perils of a dynamic pricing strategy as it specifically applies to the cultural sector.

In the simplest terms, dynamic pricing is a method whereby an organization changes the price of its admission to contemplate evolving factors such as visitor demand, price sensitivities, operational priorities, and other external factors that might influence a unique customer’s willingness to pay a unique price at any given time and date. In theory, if four of your friends went online to purchase tickets to a museum and it was deploying a dynamic pricing model, it’s possible that every one of your friends might receive a different price offer to purchase the same ticket. Dynamic pricing processes are informed by real-time data and rely on algorithmic processes and specialized software to help develop unique, changing price points that meet financial and operational criteria as established by the organization.

Dynamic pricing has long been successfully utilized in several industries. Most famously, airlines rely on dynamic pricing, and there are abundant examples in the retail, entertainment, spectator sports, and utility sectors. These sectors are able to collect, process, manage, and apply real-time intelligence concerning multiple external factors (e.g., demand, seasonality, supply chain factors, price elasticity, share of cost contribution, broad financial markers, etc.) to continuously adjust pricing conditions to be optimally responsive to these varying, ephemeral conditions.

One size does not fit most (let alone all). Data unique to your specific organization will help inform your most optimal pricing strategy.

Don’t make common mistakes when commissioning a pricing study.

This article provides an excellent 101 for the best practices related to pricing studies. Take it from an entity that does them frequently for some of our nation’s premier market leaders! No matter what company you hire, though, it’s helpful to consider some of the common pitfalls of commissioning such a study.

There are four mistakes that we commonly see cultural organizations making, and we encourage you to read more about them here:

-

- Over-reliance on comparative/competitive price precedents (“comps”). Pricing studies that rely on comps are those that say, “Hey. We are a science center. A ticket to the art museum next door is $25. The zoo across the street costs $25. And the other science center one town over is also $25.Therefore, our price should be $25.” Comps are not in and of themselves the backbone of a rigorous pricing study. Instead, they are contextual data points. Are they worth knowing? Yes. Are they foundational to understanding your organization’s pricing strategy? No.

- Over-reliance on audience research. A goal of optimal pricing is not only to engage active visitors, but also to activate inactive visitors. Inactive visitors are the folks with interest in attending your unique cultural organization, but who have not attended in the last two years or longer. To do this, an organization benefits from market research, and risks maximizing its engagement potential by relying solely (or predominantly) on audience research. When organizations neglect collecting representative market research – which often includes delivering the data in more than one language – they miss critical intel to truly understand their total market opportunity.

-

- Simplistic data inputs. The decision to attend a cultural organization is rarely an isolated one, and within the factors informing this decision, admission price is but one factor. Among people with interest in visiting cultural organizations, it’s often not even a comparatively important factor. Other factors include schedule (“Do I have time to get there after my kid’s soccer practice ends?”), travel distance and the perceived hassle of getting there at all, the growing allure of the couch, economic concerns beyond admission price, and simply how much they want to visit an organization compared to something else they’d like to do during that same precious, open afternoon. All these factors impact the perceived value of an organization’s admission price.

- Not contemplating membership alongside admission price. An admission price change often alters the price psychology surrounding your organization, including your membership offerings. When membership pricing is not contemplated alongside potential changes to an admission pricing strategy, then there is a risk of membership pricing “trailing” admission pricing. Membership pricing that doesn’t align with admission pricing can alter and influence the perceived value of membership.

What’s an appropriate, data-informed way to carry out a pricing study? Learn more here.

In sum, there are good reasons to consider your organization’s own value-for-cost perceptions and consider your data-informed, optimal admission price point. Research helps your organization uncover not only what that price point should be, but also to optimal pricing strategy for your region and desired audience. And it helps answer critical questions, such as, “To bundle experiences or not to bundle experiences…” as well as what should be included in that bundle. Research helps you understand it all, and reduce the risks of guessing and speculation, which can frustrate potential guests and backfire financially.

For those organizations contemplating price-related research, avoiding these common pitfalls will help inform an advisable scope and provide confidence in the applicability of the findings.

Back to the beginning: It’s never been more important for cultural organizations to “get their money right.” A big piece of any organization’s financial outlook is admission pricing – and it is one of the revenue inputs that data can help meaningfully inform. There is no need to rely on guesswork and vibes to inform such an important aspect of your financial sustainability.

Yours in expert analysis, real-time trends, and high-confidence research,

IMPACTS Experience