Blockbuster exhibits may be the original culprit of a top barrier to visiting cultural organizations, but the perception they’ve created extends far beyond the entities hosting them.

Have you ever asked someone if they wanted to go to a museum and heard them say, “Maybe. What’s new there?”

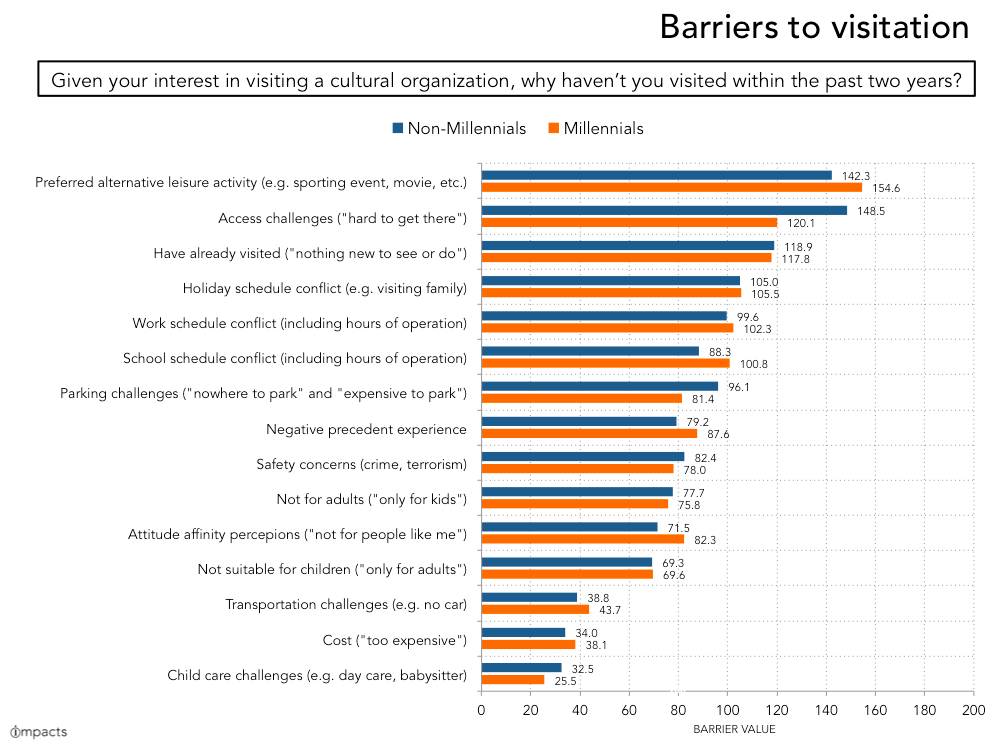

If you have, you’re not alone. Data shows “nothing new to do or see” is a top barrier to visiting cultural organizations. Frustratingly, it’s also largely a barrier of our industry’s own making.

Special exhibits and programs can help reach new audiences, provide unique experiences, and keep people engaged… but relying on these “specials” as magic bullets has created one of our industry’s biggest public perception problems. Whether your organization hosts blockbuster exhibits or not, the phenomenon that these exhibits has created is likely impacting your attendance.

The “special exhibit/program cycle” is the topic of this week’s Fast Facts video for cultural executives. While the video focuses on major special exhibits, the cycle also affects programs to reach specific audiences, the practice of offering discounts, and other “strategies” that result in intoxicating short-term attendance bumps but long-term attendance declines.

“Nothing new to do or see” is a top barrier to visiting cultural organizations

When we ask folks with interest in visiting cultural organization types why they haven’t attended, a primary reason is that there’s “nothing new to do or see,” or variances of this response such as “I’ve already visited.” This is true for both millennials and non-millennials alike at near-equal levels. (I’ve included the chart with the barriers cut out for millennials to squash the assumption that this generation’s desire for unique experiences may be driving this barrier). This data comes from the National Awareness, Attitudes, and Usage Study, which is currently over 124,000 respondents strong. It is shown in index value, which is a way of assessing proportionality around a mean of 100. Data jargon decoded: Barriers with values over 100 are the most pressing, and they serve as the most critical barriers to attendance. They are our industry’s top priorities to alleviate in order to buck the downward attendance trend and increase visitation to cultural organizations.

The perception driving this barrier is the idea that an organization’s offerings and experiences – the regular, everyday exhibitions and programs in and of themselves – are not enough to motivate a visit. This perception stems from a lack of trust that the experience will always be relevant. Visitors generally assume they’ve seen it all. After they’ve visited once, there’s little incentive to come back until there’s something new.

It may be easy to see this primary barrier and think, “well, that’s just how people are with leisure activities” – but that’s not necessarily true. We don’t see folks not attending a Cubs or Red Sox game because they’ve been to one before. Having already been to the park, on a hike, trivia night, bowling, or the beach doesn’t preclude one from coming back to do it again any time soon.

But attending a museum more than once may now need a well-publicized reason, as suggested by the overwhelming strength of this barrier to visitation. And that’s a problem. Our industry may have unknowingly created and cultivated the belief that we’re only relevant during “special” events, programs, and exhibits rather than reliably relevant all the time.

There was a line between highlighting temporary exhibits as the icing on the cake to enhance permanent experiences and making them even more important than the cake itself – and data suggests we’ve passed it.

The cycle that feeds this barrier, from an audience perception standpoint

Let’s get one thing clear from the get-go: There’s nothing wrong with special exhibits or programs. Strategically-implemented special exhibits and programs can provide effective opportunities to tell new stories, demonstrate expertise, and reach new audiences. They can be excellent tools to successfully reach desired goals. But there IS something wrong with how our industry has trained people to respond to these special exhibits and programs at the expense of permanent experiences.

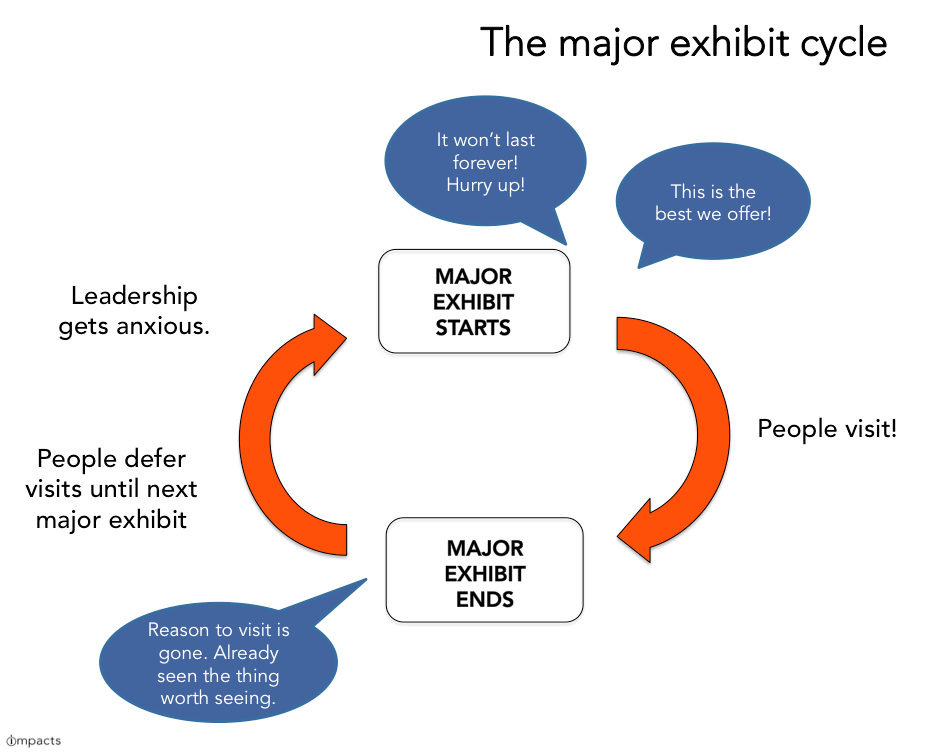

The best – albeit most extreme – way to illustrate this cycle is by considering blockbuster exhibits. The entities that host them tend to market them very heavily, much more heavily than permanent collections. From the institution’s point of view, this makes sense. Blockbusters can cost upwards of 5 or more times what an organization regularly spends on exhibits annually. The increased marketing effort is a way to maximize this investment. After all, what’s the point of having a blockbuster if you’re not going to use it to increase attendance and aim to make the money back and then some?

But think about what’s happening from an audience perception standpoint. An organization boasts a temporary blockbuster experience, and encourages people to attend. Audiences hear that this special experience is the best that the museum has to offer, so “hurry up and visit!”

And if the organization does it well, people do attend. Sometimes lots of people.

But when the exhibit is gone, so are the crowds. Now that people have seen what the museum has assured them is the best thing there, they don’t see much reason to come back until the next major exhibit. They have already seen what the museum has told them (often over and over on every platform available to them) is the primary reason to attend… and it’s gone.

When visitation slows after the exhibit ends, leadership tends to get nervous. The numbers don’t look good. The “hangover” after a blockbuster exhibit can last over two to three years. That’s a long period of time to make CEOs and board members anxious for another intoxicating attendance bump.

…So they host another major exhibit.

The cycle grows and grows, until “nothing new to do or see” becomes a top barrier to visiting cultural organizations on the whole.

Which it is now.

To make matters worse, heavily marketed special exhibits often need to be more expensive over time in order to reach the same level of attendance, making this a particularly unsustainable cycle. Not only that, major exhibits skew the visitation cycle. On average, a person who attends cultural organizations in the first place visits an organization type (such as an art museum) once every 27 months. Heavily marketed blockbuster exhibits that encourage urgent visitation put people who are likely to come back on a similar “clock.” This isn’t necessarily a bad thing in itself, but it certainly doesn’t help alleviate the “hangover” that often takes place when the major exhibit is over and attendance dips.

When organizations engage in this cycle, they tie their expertise – and the “best” of what they do – to something temporary rather than something permanent.

Permanent collections as connectors

So how do we alleviate this barrier and break the cycle? We make an active effort to let people know their time onsite will always be special. Whether there is a major exhibit or not, the goal is for people to trust that there will always be a unique, relevant experience waiting for them inside an organization’s doors.

This means remembering that permanent collections and ongoing programs matter, and they are worth celebrating as much – if not more – than expensive, temporary exhibits. The goal is to be seen as reliably relevant. It shouldn’t matter if there’s a Rembrandt collection or major motion picture-themed blockbuster at the museum or not. The aim is for people to trust that the museum will provide a unique, enjoyable experience, no matter how many times they visit or what’s on display.

This doesn’t mean setting up permanent collections and forgetting they’re there. It means celebrating them, programming them, continuing to tell their stories, and finding new ways to create meaning from them with a contemporary context. It means also – if not especially – celebrating the expertise and experience the museum provides that doesn’t leave.

Getting out of the major exhibit cycle benefits more than just attendance numbers. Despite the hype, people who visit only special exhibitions tend to be less satisfied with their experience than people who visit an organization’s permanent collections. In fact, it may be because of the hype that these satisfaction rates are lower. When we tell people to come visit immediately to see something extraordinary, the organization may need to work harder to meet heightened expectations.

Interestingly, people who visit both an organization’s permanent collections and the special exhibit have the highest satisfaction rates of all.

The related risk of one-off programs to engage new audiences

Sending the message that we are only relevant (or most relevant) on specific dates extends beyond blockbuster exhibits. This also often takes place in efforts to welcome new audiences by adding one-off programs rather than integrating a culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

For example, there seems to be an idea that a key to long-term millennial engagement is serving a themed cocktail in the gallery or atrium after hours. Sometimes this works and sometimes it doesn’t. The differentiation between the successful and unsuccessful organizations is often how well they do in underscoring how relevant they always are during the “trial” in which those millennials are onsite.

When an organization highlights a program as the primary or only reason for millennials (for instance) to visit, then then the organization’s unintentional message is, “We’re only of interest to you during these specific programs – not all the time.” Sometimes, an organization will simply highlight the next “millennial” event while they have new audiences onsite, potentially aggravating the cycle.

While reminding folks of the next event may be a smart move, there’s merit to using the opportunity to show these visitors why you’re relevant to them all the time. This may mean setting up the event in an engaging permanent exhibit space, programming around the event based on the entity’s expertise, or even pointing them toward other, regular programming that isn’t specifically millennial-targeted in addition to that millennial-targeted event.

To each their own, but most entities probably don’t want people to have to wait until another specific program to feel welcome again.

Special exhibits and special programs can be critical avenues for engagement – and the argument here is not to stop doing them by any means! Special exhibits can be critical ways to stay relevant, but they shouldn’t be the entirety of what makes a healthy institution relevant.

We are tracking this cycle amongst several organizations in the US – particularly in regard to expensive, blockbuster exhibits. …And you don’t need us to name those caught up in the costly cycle. Sometimes cultural organizations are so focused on annual timeframes they become addicted to the attendance bump of a successful blockbuster, and overlook the long “hangover” that can last years after the blockbuster exhibit ends. The blockbuster exhibit cycle can be devastating when not approached strategically and without broad understanding of the cycle.

This cycle is a reality for our industry, whether your organization hosts blockbusters or not. But it’s not a necessity. We can overcome it by remembering that permanent collections and ongoing offerings are the cake, and temporary “specials” are the icing – not the other way around. “Specials” are not effective band-aids for a lack of institutional relevance.

What makes an organization relevant is embedded in its culture, values, expertise, permanent collections, and ongoing programs.

It’s the things that don’t leave.

Nerd out with us every other Wednesday! Subscribe here to get the most recent data and analysis on cultural organizations in your inbox.