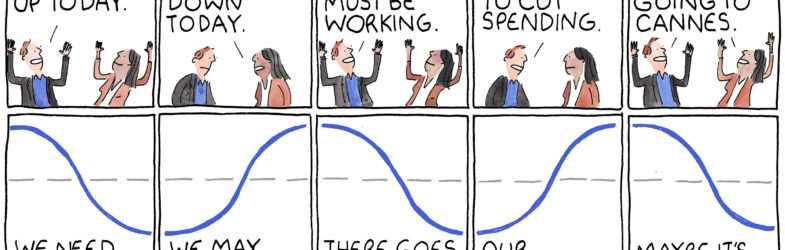

Some cultural executives still aim for short-term attendance spikes at the expense of long-term financial solvency - and they may not even know it.

Annualized calendars reward short-term attendance quick hits, and risk making cultural organizations blind to opportunities for long-term sustainability. It's a big problem - and it's one that may keep plaguing us until we get it right...or at least start emphasizing appropriate timeframes that better enable visitor-serving organizations to best achieve financial goals. It's an issue of short-term, low stakes vs. long-term payoff for cultural organizations. Annualized timeframes make it very difficult to achieve long-term success because...Never miss the latest read on industry data and analysis.

Already have an account? Sign In