What role do museums play in today’s world of mixed messages and “alternative facts?” A pretty big and important one, according to research.

We last shared data on how much people trust museums about two years ago. At that time, we were only dipping our feet into a world of “alternative facts.” This is a metric we at IMPACTS are watching closely as cultural organizations struggle with politicized issues – and as the idea of “trust” may be changing among people living in the United States.

As it turns out, trust in museums remains high:

This Fast Facts Video For Cultural Executives shares the data update, cut through the end of 2018 from the National Awareness, Attitudes, and Usage Study. Keep your eyes peeled, as you’ll see this fresh data cut again in AAM’s Center for the Future of Museum’s TrendsWatch Report coming your way later this month.

Museums are trusted. They are seen as more credible sources of information than newspapers, other NGOs, and – by particularly large measure – federal agencies.

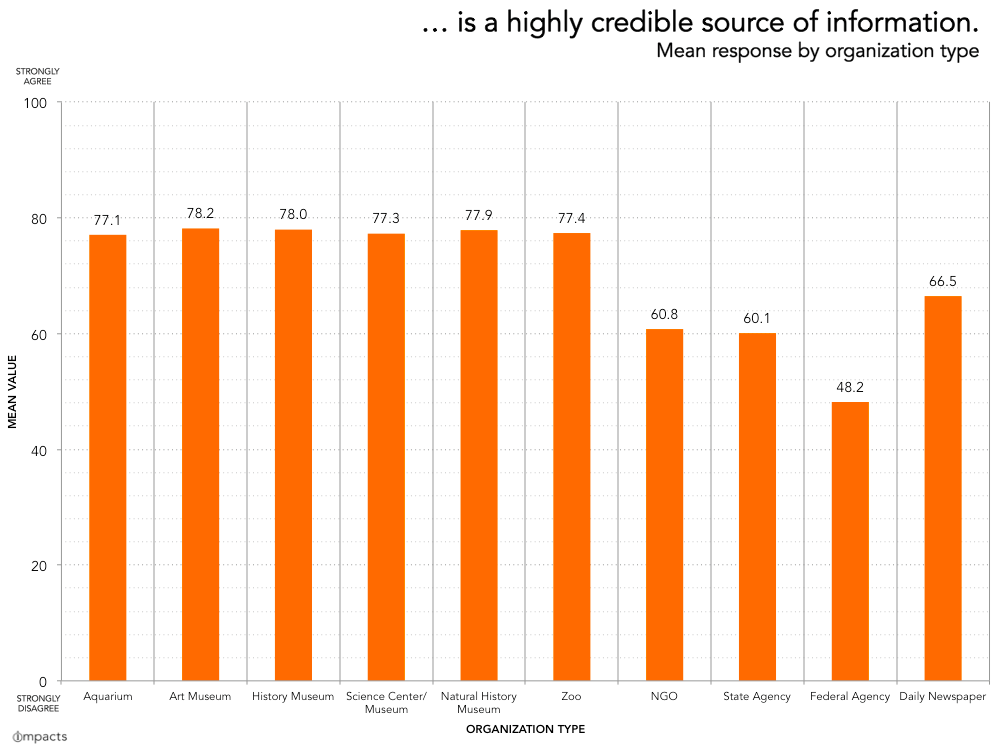

Just how trusted are museums compared to other entities? Let’s take a look. For context in these charts, values over 64 begin to show agreement, and values below 62 begin to show disagreement.

1) Museums are highly credible sources of information

Let’s start by looking at how the perceived credibility of different entities stacks up against one another. The NGO category includes non-governmental organizations that are not museums. The mean value of 60.8 (down sharply from 64.2 two years ago) for NGOs indicate a relative lack of credibility with perceptions largely influenced by the degree to which the NGO conforms to the respondent’s worldview. For example, no matter what the integrity of the information published by the Natural Resources Defense Council, an avowed climate change denier is unlikely to find the NRDC credible. State agencies have also lost credibility, with a value of 60.1 (down from 61.3). Federal agencies (with a mean value of 48.2, down from an already-low 51.4) represent an even more bifurcated public view – which makes sense in our current partisan condition.

With a value of 66.5, daily newspapers (as a category) are generally seen as highly credible sources of information among the US public.

But check out museums! Aquariums, art museums, history museums, science centers/museums, natural history museums, and zoos have values in the high 70s! As scalar variables go, these numbers are worth noting! Not only that, these numbers are markedly similar to values recorded two years ago.

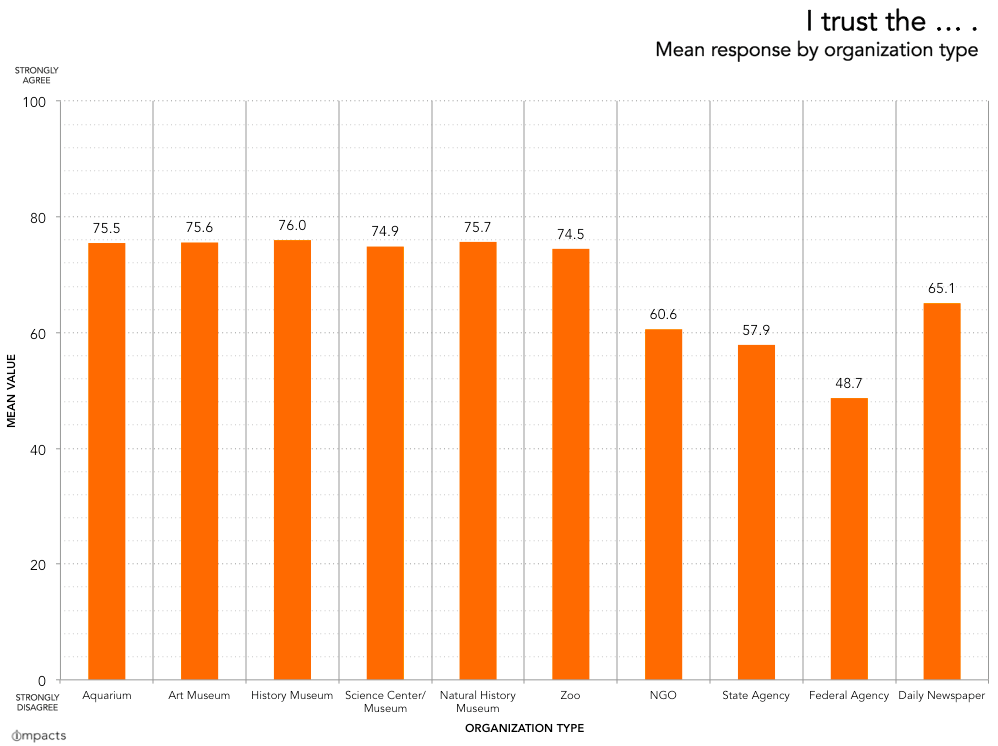

2) Museums are trusted

People also trust museums. This level of trust is not to be taken lightly, and it’s a testament to organizations that stand by their missions to educate and inspire audiences. It may also be argued that museums are trusted because they employ and/or consult topic experts and thus provide credible content.

Zoos and aquariums are trusted. I point this out because it lends context to some debates taking place in the zoo and aquarium world regarding captive animals. Research reveals stark trend lines regarding perceptions of exhibits such as dolphin shows, but people still largely trusts zoos and aquariums to evolve and make value-based decisions driven by their missions. While these organizations may be facing issues regarding aspects of captivity, they are also pulling for plastic bag bans keep the ocean safe and clean, and executing animal rescue, rehabilitation, and release efforts. How organizations handle sticky situations maybe be more telling than not having to face them at all.

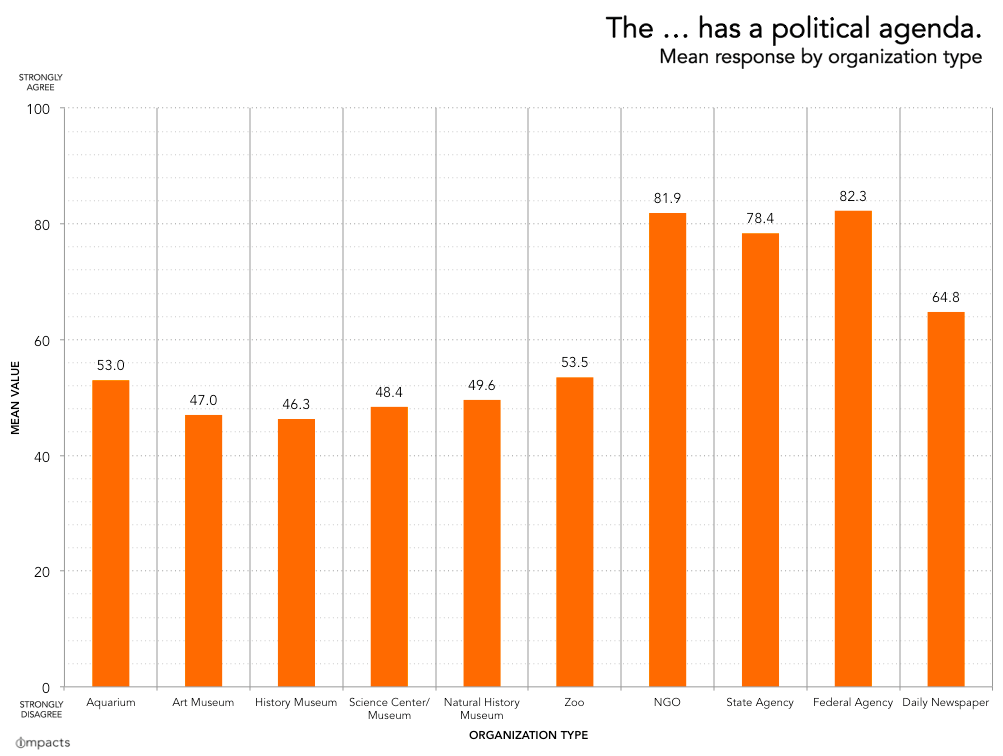

3) Museums are not seen as having political agendas

Some organizations take up issues that their leaders may worry are overly politicized. Some talk about climate change and human evolution, or have missions to bring together specific diverse, underserved, and underrepresented communities. Despite these efforts, however, people do not view museums as having a political agenda.

Are museums trusted because they are not seen as having political agendas? Maybe, but maybe not. When an organization’s mission itself may be viewed as “politicized,” where does an organization draw the line? What’s an organization to do when facts become politicized?

Taking a political stand for the sake of taking a political stand seems like mission drift for most organizations, but taking a stand for an organization’s mission may be different. Recent happenings suggest that when an organization’s mission is pinned against a politicized topic, standing up for your mission wins. MoMA, for instance, protested the original Muslim-majority nation travel by highlighting artwork by artists from the impacted countries – and data demonstrated how favorably their gesture was received.

Museums are increasingly taking up issues that are in line with their missions – marching in pride parades in the name of inclusion, hosting naturalization ceremonies, and reminding the public that facts matter. And yet, people generally do not view museums as having a political agenda any more than they did two years ago!

Museums are viewed as impartial entities, and this may be because they are trusted to present the facts with expertise, as they related to their stated missions.

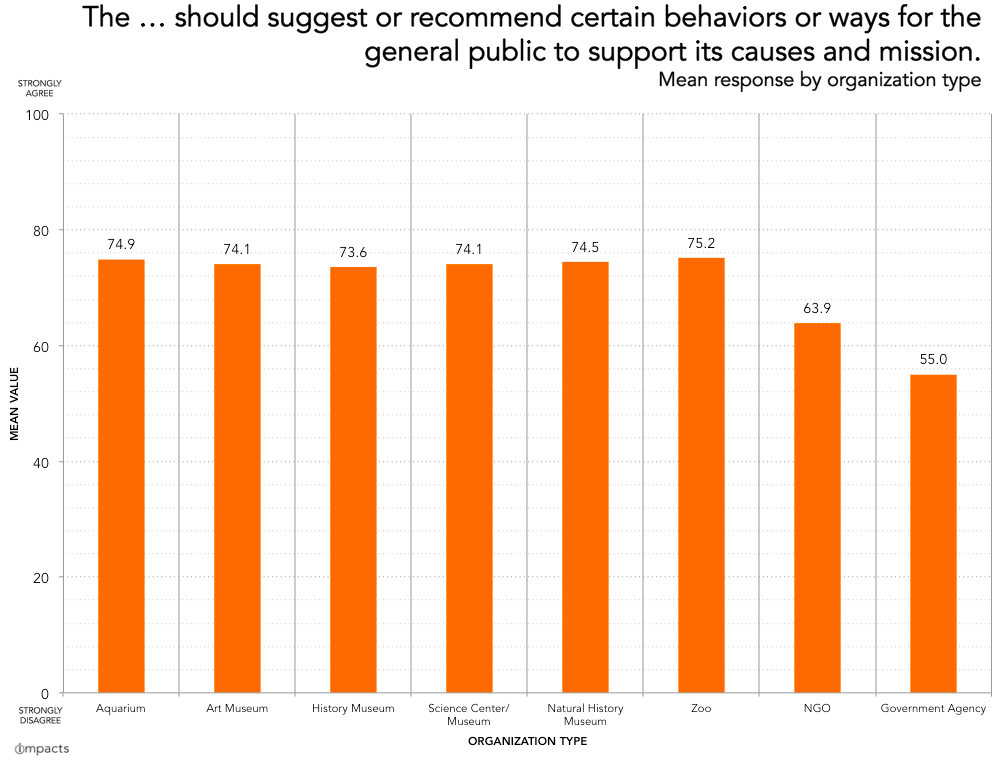

4) People believe that museums should recommend action for their missions

This data set may be the most important – and the findings are especially similar to two years ago. People believe that museums should suggest or recommend certain behaviors or ways for the general public to support their causes. This is likely tied to the combined force of the high levels of trust and credibility that these organizations possess.

Consider that recommending action is not the same as “being political.” Recommending things like cutting down on single use plastics (as a zoo or aquarium may advise) or contributing funding for art programs (as an art museum may recommend), may not be seen as necessarily “political” to people, but rather as an organization walking its talk in terms of supporting its mission.

Museums have a responsibility to be the superheroes for not-alternative facts. Museums, zoos, and aquariums are highly trusted to produce and output content and information. They are viewed as expert, factual, and impartial – more so than government agencies and even daily newspapers. People – who generally don’t like to be told what to do – are even willing to accept prescriptive recommendations from museums.

This doesn’t necessarily mean endorsing political candidates or taking up purposefully politicized issues that don’t relate to an organization’s mission is a smart move. Preserving trust levels may mean the opposite. It may mean that it’s museums’ responsibility to stand up for their missions, and to figure out where to draw the line. If standing up for a cause is a good thing, then “opting out” of mission impact – when it’s threatened – may be viewed as untrustworthy. It’s worth mentioning that being trustworthy and credible – in and of itself – does not necessarily mean anything related to politics at all. It relates to expertise and integrity.

Museums are trusted sources of highly credible information today, and people expect them to be advocates of their missions and causes.

We have a superpower. Let’s use it when appropriate to make the world better.

Nerd out with us every other Wednesday! Subscribe here to get the most recent data and analysis on cultural organizations in your inbox.