Want to keep moving your mission moving forward and your doors open? It’s time to end the debate on these pricing-related topics.

As the visitor-serving industry (museums, theaters, symphonies, historic sites, etc.) broadly struggles with declining attendance trends and a potentially unsustainable reliance on kindness and not commerce, “getting your price right” is more important than ever to nonprofits who depend on the gate to support their missions. Too high of a price may serve as a barrier to visitation. Too low of a price risks leaving money on the table and all of the attendant fiscal challenges associated with failing to maximize earned revenues.

Much is happening in the world that changes/challenges the way that traditional visitor-serving nonprofits operate: social media and technology, the need for real-time transparency, and changing demographics in the United States and beyond are just a few, prominent factors influencing our industry. And, these factors are changing everything from internal operations to membership products and the role of fundraising. And, unsurprisingly, the information age requires embracing new realities related to pricing.

Let’s end the debate on these three pricing-related topics and get on with the business of running effective businesses that enable meaningful missions:

1) Pricing is NOT an art (Pricing is now a science)

Determining the optimal price of admission is no longer a trial and error process. In fact, it’s anything but a “guess” (however well-educated). Data is playing an increasingly important role in the way that institutions operate for good reason.

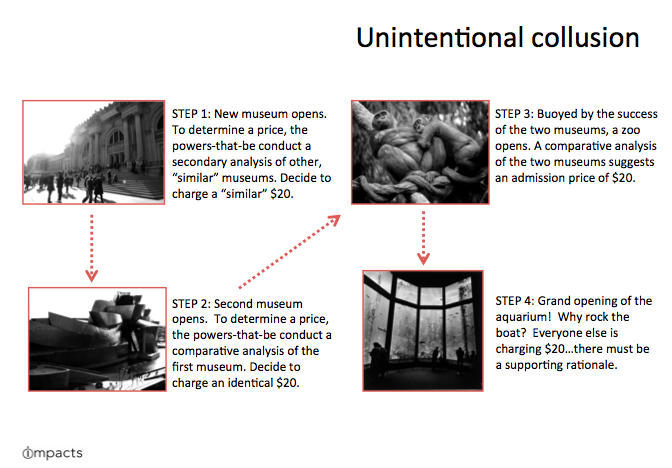

A near-decade of research including hundreds of interviews with US visitor-serving nonprofit organizations strongly suggests that many pricing models are the product of “unintentional collusion” (AKA “the blind leading the blind”). This deeply-flawed model fails to contemplate two critical factors when it comes to informing a pricing strategy: (i) the fact that a proximate (or competitive, or peer) organization has established a price does not necessarily mean that it is an optimal price; and (ii) the market tends to view organizations – however “alike” they may be – in very unique terms, and this uniqueness frequently extends to pricing.

Unintentional collusion looks something like this:

Thanks to readily available data and analyses, there is no reason to base pricing on anything beyond an organization’s own, unique equities. For every organization, there is a data-based “sweet spot” in which admission prices are optimal.

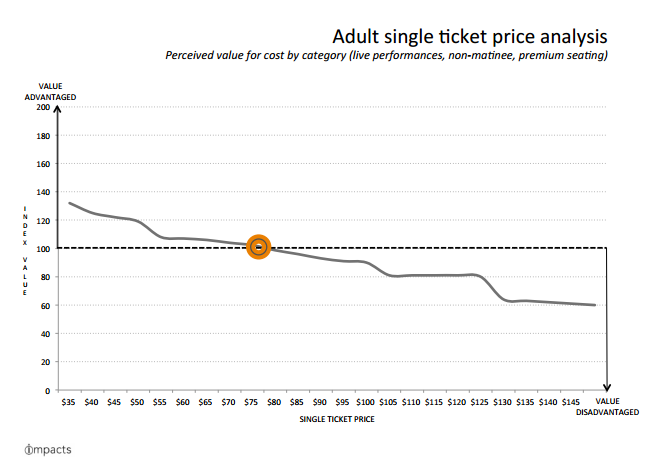

Let’s consider a quick example of what an optimal pricing strategy looks like when charted (Note: This particular example is from a performance-based entity, but this way of considering pricing applies to any type of admission):

In the above example, the data-informed analysis suggests that pricing less than $75 for a ticket to the performance (more specifically, to a “premium” seat at a non-matinee, live performance) would be “value advantaged” – a polite euphemism for leaving money on the table! However, anything above $75 pushes the price into the “value disadvantaged” realm – a place where the price poses a needless barrier to entry (and, generally, one where the increased per capita revenues will not offset the decline in attendance). For every category of admission, every organization has an optimal price – one that is neither value advantaged nor value disadvantaged.

Organizations guess their price (without leveraging data to inform their pricing strategy) at their own risk. Getting the price wrong can alienate potential visitors and supporters if it’s too high, and make it difficult to raise prices to an optimal value over time if price starts too low.

Looking for ways to help support a price increase? Well, data suggest that a whiz-bang new exhibit or facility expansion isn’t necessarily coupled to an increased price tolerance. Instead, efforts to improving an organization’s reputation or the overall satisfaction of visitors are much more reliable indicators of increased value for cost perceptions.

2) Admission pricing is NOT affordable access (Admission enables affordable access)

A thought that sometimes emerges once an organization’s optimal pricing has been quantified is strangely, “but that’s too expensive to provide affordable access!” Admission is not a substitute for affordable access. Admission and affordable access programs are completely different things…and an organization needs to establish its optimal pricing strategy in order to support effective affordable access programming.

In other words, if you subsidize price in the name of affordable access (i.e. artificially lowering the price to create a value advantaged pricing condition), you are limiting your organization’s ability to fund quality programs that DO provide true affordable access. Making your entire pricing strategy an “affordable access program” leaves money on the table as folks pay an admission price below what they (the market!) indicate they were willing to pay for your experience.

When it comes to the truest definition of affordable access, an admission price point of $15 or $20 or $25 is functionally irrelevant to many of our most under-served audiences…most any price at all may pose an insurmountable barrier to visitation.

What if you aim to provide affordable access for the community? Won’t a high admission price deter folks? The data suggest “no” – at least not the people who were able to pay in the first place – but that doesn’t mean it’s not a good idea to develop true access programming to better engage constituents for whom price is barrier while also considering strategic promotions that celebrate your community. Speaking of which…

3) Discounts are NOT promotions (Promotions serve a purpose beyond cheap access)

Promotions celebrate community while discounts devalue your brand. These are very real and very different things. The biggest differentiating factor is the question “So what?” If the point of providing a discount is simply admitting folks for a lower price, then the discount is a bad idea that devalues your brand. (And, as a reminder, data suggests that all discounts provided through social media are bad business for nonprofit organizations.) However, if an organization’s answer to “so what?” is “to celebrate a community” and that purpose is made clear in external communications, then the program that you are describing is a promotion. The feature of a promotion may include a special pricing opportunity – think special pricing for mothers on Mother’s Day, or differentiated pricing for local residents.

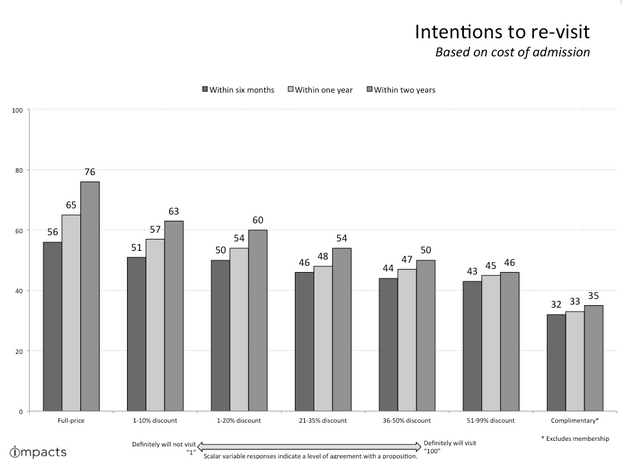

Discounts make people say, “I got in cheap.” Promotions make people say, “I feel valued.” Discounts are not only meaningless, but data suggest that they also lead to less satisfying overall experiences and even increase the time before a return visit! While this may be surprising to some folks, it’s classic pricing psychology in action.

If visitor-serving organizations aim to keep providing inspiration and education to the masses, then the first imperative is to exist – and it’s hard to exist (let alone thrive) in the long-term without a sustainable revenue strategy that optimizes pricing.

Pricing strategies – and even pricing psychologies – are not mysterious so let’s stop guessing.