There’s significant data compiled by multiple sources indicating that “getting discounts” is the top reason why people engage with an organization’s social media channels. So it seems logical that if you want to bump your number of fans and followers, offering discounts is a surefire way to go. And it works – if your sole measure of success is chasing these types of (perhaps less meaningful) metrics. But, before you go crazy with the discount offers on Facebook and Twitter just to get your “likes” up, here’s another thing that’s true: Offering discounts through social media channels cultivates a “market addiction” that will have long-term, negative consequences on the health of your organization.

I recently wrote a post called “Death by Curation” within which I shared data indicating the non-sustainable cycle that museums enter when they must rely on new, progressively more expensive “special” exhibits in the hopes of achieving attendance spikes (what has since been referred to by a reader of this blog as “Blockbuster Suicide”). In many ways, offering discounts creates a similarly vicious cycle whereby a visitor-serving organization finds itself realizing a diminishing return on the value of its visitation.

When an organization provides discounts through social media it trains their online audience to do two not-so-awesome things:

1) Your community expects more discounts

Here’s where your organization breeds an online audience of addicts accepting discounts…and, strangely enough, becomes addicted to offering discounts itself. Posting a discount to attract more likes on Facebook (or to get people to engage with a social media competition, etc.) will very likely result in a bump in likes and engagement. But know that in doing this, you are verifying that your social media channel is a source for discounts. Discounting for “likes” attracts low-level engagers (they are liking you for your discount, not your mission), and prevailing wisdoms increasingly suggest that your number of social media followers doesn’t matter. It is far better for your brand and bottom line to have 100 fans who share and interact with your content to create a meaningful relationship, than to have 1,000 fans who never share your message and liked you just for the discount.

I can hear the rumbling now: Some of you are thinking, “But we’ve used discounts to attract more likes and it worked” (i.e. it generated more likes). Over time, however, these low-level engagers will stop following you if you do not continue to offer discounts. That is, after all, the reason why they followed you in the first place…and you have shown them that, yes, you will post discounts on social media. This is the start of the addiction: In order to keep these likes, you need to offer more discounts.

Try this: Simply stop offering discounts. Over the course of a few months, your number of likes will go down (because these people only liked you for the discount, not your awesome, socially conscious content). They were not actual evangelists – and cultivating real evangelists to build a strong online community is the whole point of social media. You want folks who actually care about what you’re doing and will amplify your message (not the “we are offering a discount” message – which is the content that, unfortunately, frequently gets the most shares and perpetuates this cycle).

2) Perhaps more importantly, your community waits for discounts

Here’s where becoming an addict takes a toll on the organization’s health. Data indicates that offering coupons on social media channels – even once – causes people to postpone their visits or wait until you offer another discount before visiting you again. Worse yet, the new discount generally needs to be perceived as a “better” offer (i.e. an even greater discount) to motivate a new visit. This observation is consistent with many aspects of discount pricing psychology, whereby a stable discount is perceptually worth “less” over time. In other words, the 20% discount that motivated your market to visit last month will likely have a diminishing impact when re-deployed. Next time, to achieve the same outcome, your organization may have to offer a 35% discount…and then a 50% discount, etc. You see where I’m going with this…

Here is the debunking of another popular misnomer that some organization’s use to justify their discount tactics: You are not necessarily capturing new visitation with discounts. In fact, data from the company for which I work suggests that the folks using your discount were likely to visit anyway…and pay full price! This is a classic example of an ill-advised discounting strategy “leaving money on the table.”

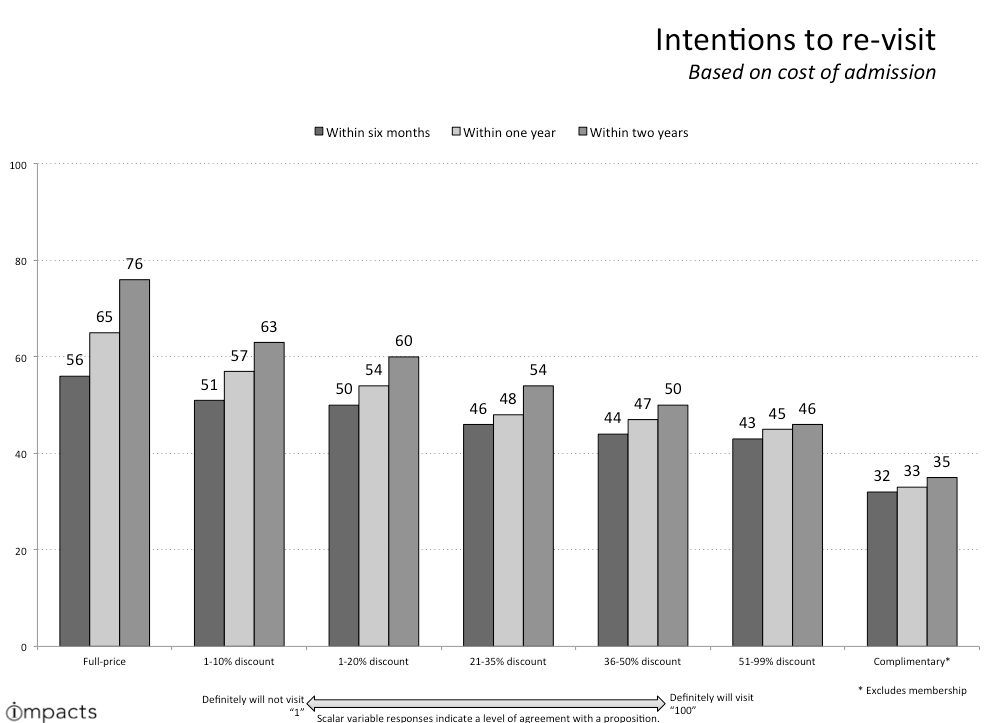

To compound matters, instead of hastening the re-visitation cycle, the “waiting for a discount” phenomena may actually increase the interval between visits for many visitors. The average museum-going person visits a zoo, aquarium, or museum once every 19 months. If you offer a discount, while you may not attract a larger volume of visitation to your organization, you may accelerate your audience’s re-visitation cycle on a one-time basis. This sounds great…until you realize the significant downsides to this happening: Your audience just visited your organization without paying the full price that they were actually willing to pay and they likely won’t visit your organization again for (on average) another 19 months. On top of all this, IMPACTS data illustrates that the steeper the discount, the less likely visitors are to value your product and return in a shorter time period.

Think of it this way: A visitor coming to your museum in May 2012 would likely visit again in December 2013 (i.e. in 19 months). Let’s say that you offer them a discount that motivates them to visit in October 2013. Now, you’ve linked their intentions to visit to a discount offer…and decoupled it from what should be their primary motivation – your content! And, by doing so, you’ve created an environment where content as a motivator has become secondary to “the deal.” In other words, you will have moved your market from a 19-month visitation cycle to a visitation cycle dependent on an ever-increasing discount. Can your organization afford to keep motivating visitation in this way?

So, how do museums get addicted to discounts, too? Well, we sometimes confuse the response (i.e. a visit) to the stimuli (i.e. a discount) with efficacy. Once a discount has been offered to motivate a visit, we regularly witness the market “holding out” for another discount before visiting again. And what are museums doing while the market waits for this new discount? Sadly, often times the answer is that they are panicking.

If you run a museum, you’ve probably spent some time in this uncomfortable space – we observe the market’s behavior (or, in this case, their lack of behavior), and begin to get anxious because attendance numbers are down. What’s a quick fix to ease the pain of low visitation? Another discount! So we offer this discount…and, in the process, reward the market for holding out for the discount to begin with. This is the insidious thing about many discounting strategies: They actually train your audience to withhold their regular engagement, and then reward them for their constraint. We feed their addiction and, in turn, we become addicted ourselves to the short-term remedy that is “an offer they can’t refuse.”

Like most addictive – but ultimately deleterious – items, there is no denying that discounts “work” – provided that your sole measure of the effectiveness of a discount is its ability to generate a short-term spike in visitation. But, once the intoxicating high of a crowded gallery has passed, very often all that we’re left with is a nasty hangover. My advice to museums and nonprofit organizations contemplating a broad discount strategy on social media: Just say no!