Museums often develop a cycle wherein they rely heavily on visitation from special exhibits – rather than their permanent collections – in order to meet their basic, annual goals. This is a case of “death by curation” – bringing in bigger and bigger exhibits in order to keep the lights on. Museums often fail to recognize that the best part of the museum experience, according to visitors and substantial data, is who folks visit and interact with instead of what they see. Understanding that a museum visit is more about people than it is about objects can help museums break the vicious cycle of “death by curation,” and help them develop more sustainable business practices.

The Myth of the Special Exhibit Strategy

It’s no secret that a true blockbuster exhibit can boost a museum’s attendance to record levels. However, a “blockbuster” is rare, and the fact that these blockbusters spike attendance so dramatically is an important finding: Blockbusters are anomalies – NOT the basis of a sustainable plan.

We know the story well: a museum decides to host an exhibit and develops exhibit-related messaging to promote visitation to the exhibit. The museum sees a spike in attendance, which dips when the exhibit closes. The museum wants to hit these high numbers again so it hosts a “bigger” exhibit and hopes for the same visitation spike.

This is the beginning of a costly, ineffective cycle. Here are two misbeliefs that perpetuate this less-than-sustainable practice:

1. The museum comes to believe that it cannot motivate visitation without rotating increasingly “blockbuster” exhibits. And, by doing this, museums train their audiences only to visit when there is a new exhibit. Thus, they risk curating themselves into unsustainable business practices.

2. If the museum is successful with this strategy of rotating blockbuster exhibits, then the exhibits grow grander (it’s hard to keep improving on a “blockbuster” – have you ever known a sequel to cost less than the original?), and the attendant costs grow at unsustainable rates…but become conceptually necessary for the museum to keep their lights on.

What of the hopeful thought that visitors to blockbuster exhibits will become regular museum-goers? It is largely a myth. An IMPACTS study of five art museums – each hosting a “blockbuster” exhibit between years 2007-2010, found that only 21.8% of visitors to the exhibit saw the “majority or entirety” of the museum experience. And, of those persons visiting the sampled art museums during the same time period, 50.5% indicated experiencing “only” the special exhibition. This data indicates that these special exhibit visitors are not seeing your permanent collections and, thus, are missing an opportunity to connect with your museum and become true evangelists.

Even members, whom museums often assume are more connected to their permanent collections than the general public, have been trained to respond almost exclusively to “blockbuster” stimuli. To wit: The National Awareness, Attitudes and Usage Study recently completed in April 2011 indicates that of lapsed museum members with an intent to renew their memberships, 88.6% state that they will renew their memberships “when they next visit.” Of these same lapsed members, 62.5% indicate that they will defer their next visit “until there is a new exhibit.” In other words, museums have trained even their closest constituents to wait for these expensive exhibits in order to justify their return visit.

Case Study

I like to think of this as a sort of “Pavlov for the museum world” – except instead of inspiring behavior with a bell, we’ve decided to provide Monet, Mondrian and Picasso as stimuli. This is all perhaps well and good…but it isn’t sustainable.

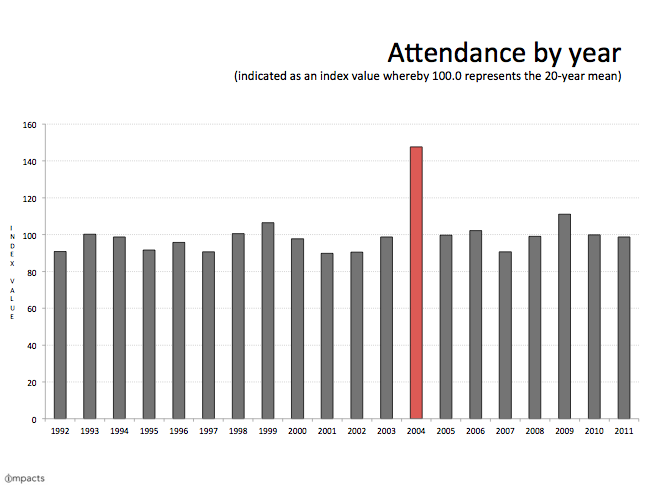

Consider the 20-year attendance history of a museum client of IMPACTS (the company for which I work). Can you spot the “blockbuster” year?

In this example (which I selected because it is representative of the experience of many museums), the “blockbuster” exhibit of year 2004 resulted in a 47.6% spike in visitation. But, what is perhaps most telling is how quickly – post-blockbuster – the client’s annual visitation returned to its average level. Does this suggest that the client shouldn’t pursue another blockbuster? Well, they did. But, not with the expected results.

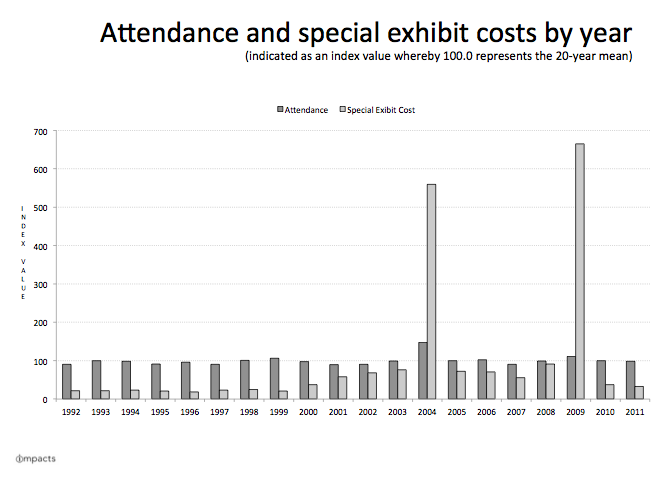

Let’s consider the same chart again – this time with the special exhibits costs by year also indicated:

Still drunk with success from their blockbuster exhibit in year 2004, this museum went to the “tried” (but, not necessarily, “true”) blockbuster formula in year 2009. As you can see, in terms of visitation, history decidedly did NOT repeat itself. This where it becomes additionally important to acknowledge that “expensive does not a blockbuster make.”(See the domestic box office receipts of “John Carter” for recent proof).

Another fun fact that will surprise absolutely no one in the museum world – audiences are fickle! Their preferences shift quickly and they become increasingly hard to please. In fact, first-time-ever museum visitors rate their overall satisfaction 19.1% higher than persons who have previously visited any other museum. In my business, we call this “point of reference sensitivity” – the market’s expectations, perceptions and tolerances are constantly shifting and being re-framed by its experiences. Think about it yourself: The FIRST kiss goodnight – a forever memory! The hundredth kiss goodnight – (still sweet, but) been there, done that.

Break the Cycle: Invest in People and Interactions

Knowing that who a visitor comes with is the best part of visiting a museum provides power for museums to break this cycle.

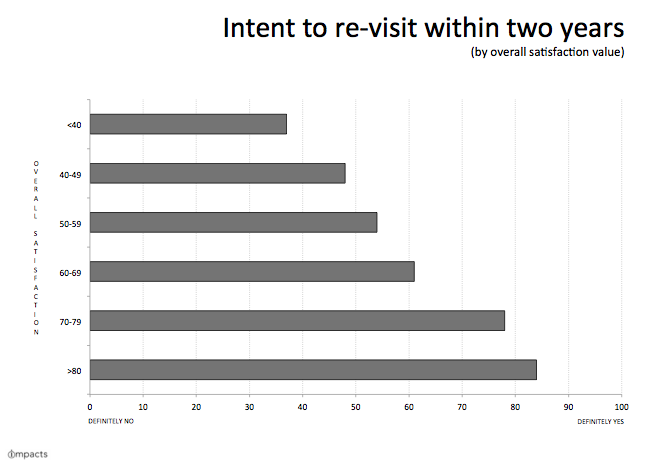

Instead of relying on the rotation of expensive exhibits, many successful museums instead invest in their frontline people and provide them with the tools to facilitate interactions that dramatically improve the visitor experience. Improving the visitor experience increases positive word of mouth that, in turn, brings more people through the door. Importantly, reviews from trusted resources (e.g. WOM) tend to not only inspire visitation, they also have the positive benefit of decreasing the amount of time between visits. In other words, people who have a better experience are more likely to come back again sooner.

The power of with > what has other positive financial implications for museums. If the institution focuses on increasing the overall experience (which, again, is a motivator in and of itself – as opposed to the “one-off effect” of gaining a single visit with a new exhibit), then the museum’s value-for-cost perception increases. In other words, it allows the museum to charge more money for admission without alienating audiences because these audiences are willing to pay a premium for a positive experience.

(For you mission-driven folks shaking your head about how this potentially excludes underserved audiences, this is where your accessibility programs will shine. It allows them to be more effective and increases their perceptual value as well.)

This isn’t to say that new content and engaging exhibits are not critical to a museum’s success. It is to say, though, that times are changing. To sustain both in terms of economics and relevance, museums must evolve from organizations that are mostly about “us” (what we have is special and you’re lucky to see it), to organizations that are primarily concerned about “them” – the visitors.

Like it or not, the market is the ultimate arbiter of a museum’s success. Those of us with academic pedigree, years of experience, and technical expertise may well be in a position to declare “importance,” but it is the market that reserves the absolute right to determine relevance. In other words, while curators still largely design the ballots, it is the general public who cast the votes. And, in the race to sustain a relationship with the museum-going public, the returns are in and the special exhibit isn’t so special anymore.

Note: I have since written a more updated article on this topic featuring the same data. You can read the article here.