As the US population grows, the number of people attending visitor-serving organizations is (still) in general decline. And this is a very big problem for sustainability without a digital-age shift in our business model.

It’s not just museums. Many visitor-serving organizations – science centers, historical sites, aquariums, zoos, symphonies, etc. – are failing to keep pace with population growth.

Consider: In the five-year duration spanning 2009-2013, the US population increased by 3.5% from 305.5 million to 316.1 million. The majority of this growth occurred in major metropolitan areas – the very population dense regions where many visitor-serving organizations are located. Indeed, nearly one in seven Americans live in the metropolitan areas of the country’s three largest cities – New York, Los Angeles and Chicago.

However, during the same duration, data indicate that attendance at many nonprofit, visitor-serving organizations has declined. In fact, of the 224 visitor-serving organizations contemplated in the 2014 National Awareness, Attitudes & Usage Study of Visitor-Serving Organizations (NAAU), 186 organizations (83.0%) reported flat or declining attendance. And this is neither a regional nor curatorial content-specific finding – the study representatively contemplates visitor-serving organizations of every size, type, and area.

Many organizations are hesitant to acknowledge attendance challenges…especially when they have historically cited being the “most visited” as an indicator of their expertise and effectiveness. I sense that pressure from governing boards also plays a role – particularly as many organizations have been tasked to maximize earned revenues (often inevitably linked to visitation). Perhaps most concerning of all are attempts to blunt the challenge by proposing half-measures as remedy – you’ll no doubt recognize the “don’t worry, we’re going digital!” excuse and the related practice of sending mid-level staff to innovation conferences as attempted evidence of progress. (This last excuse may be especially worrisome as it seems that many staff members tasked to “innovate” may not actually be empowered to carryout their plans for advancement.)

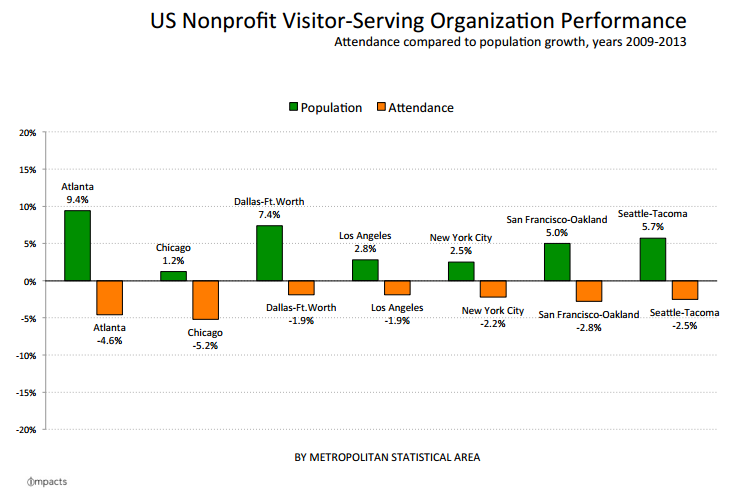

But, regardless of the excuse, the numbers suggest that our industry risks becoming less relevant to future audiences. What does this mean to visitor-serving organizations? Let’s look at a few examples. (Note: To keep this from being a huge, overwhelming chart, I pulled out major metro markets and a few areas cited as “up and coming.”)

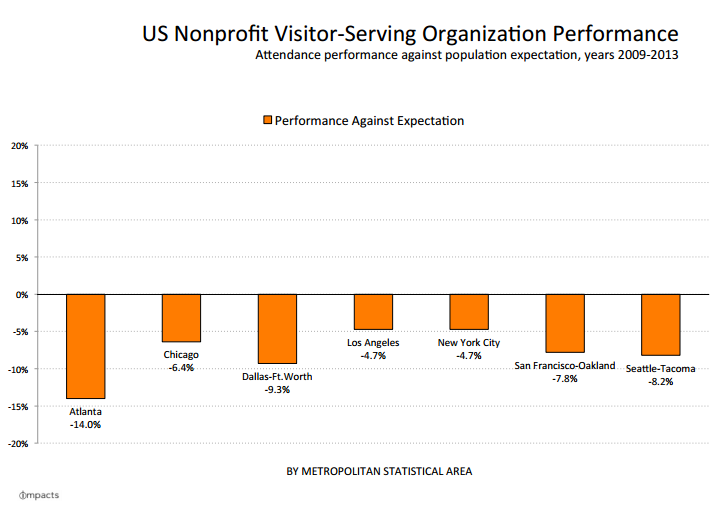

To illustrate, the population of the Atlanta, GA Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) has increased in the past five years by 9.4%. During the same duration, visitation to the Atlanta-area organizations contemplated in the NAAU study indicates an attendance decline of 4.6%. Think about that – if engagement were keeping pace with population growth, an organization with an annual attendance of 1,000,000 in year 2009 would reasonably expect to welcome 1,094,000 visitors in year 2013. Instead, on average, the studied organizations saw attendance decline from the theoretical 1,000,000 visitor level in year 2009 to 954,000 visitors in year 2013. Measured against the expectations of population growth, visitor engagement underperformed by 140,000 visitors!

The expectation would be for attendance to increase alongside population growth – otherwise, it is indicative of underperforming the opportunity. Again, the findings are stark and concerning for organizations in the engagement business:

In most any other business, if you saw the market steadily increasing in size and your product’s usage in steady retreat alongside it, you’d likely think, “This business model sucks.”

Well, our business model sucks.

Confronted with this evidence, I’ve heard leaders recycle tired strategies of securing larger donations from an aging donor base, and plans to gain more grant funding from governments and foundations. Generally, they aim to “pivot” from a reliance on earned revenues to (hopefully…fingers crossed!) additional contributed revenues. Except no. The visitor-serving industry doesn’t need to pivot. It needs to reset.

Here are three behaviors we need to adapt to reset our current condition:

1) Stop citing poor previous efforts as evidence that something will not work

Some visitor-serving organizations will declare that they “already tried” something after investing only the most minimal of resources necessary to claim effort. This is a surefire recipe for failure …yet, it happens all of the time. Here’s a quick example: Many organizations will offer options to buy tickets online and simply invest enough to create a webpage for it. Then when nobody uses that method to buy tickets they say, “Look! We tried that and nobody bought tickets that way!” Actually, nobody bought tickets that way because your site wasn’t mobile friendly, it takes 10 different screens to buy a ticket, it requires several pages of personal information, it’s confusing and time consuming, and it costs more. Often it’s an organization’s own fault when data-informed things don’t work, but organizations frequently take a half (or maybe a one-tenth) approach to something and basically (knowingly or unknowingly) set it up for certain failure. This is just one, basic example.

“Our crummy product failed, ergo everything related to this project won’t work” justifies stagnancy by masking it with false wisdom. Organizations think that they are cutting-edge for trying something without any conviction, and that the wisdom they received from their inevitable failure justifies closing the book on really big things like digital engagement. How does this even make sense? This type of excuse-making is a shortcut to irrelevance. Just stop doing it.

2) Stop defending past decisions

This seems to be a particularly hard one for many leaders to embrace. After all, it may be human nature to defend one’s past decisions as “right” and “good.” And, at the time when they were made, they probably were. But times change. Today, we are witnessing incredible changes – many borne of technological advancement – accelerating progress at a revolutionary pace. By what rightful reason do we think that we’re exempted from the prevailing changes affecting the rest of the world?

Just because you spent thousands and thousands of dollars on print material doesn’t spare you from the necessity of hiring an online community manager. On a more substantial investment scale, those millions of dollars that you invested in a new entrance to facilitate faster put-through times doesn’t exempt you from developing a mobile ticketing platform that may make ticket counters increasingly obsolete. This is a lesson to learn in real-time (as opposed to retrospectively): Repairing and updating past decisions is often more time-consuming and, ultimately, more expensive in the long run than starting anew. It’s OK – heck, even encouraged – to approach the current condition untethered to the past. That was then, this is now.

3) Embrace the inevitable path of progress

Max Anderson, CEO of the Dallas Museum of Art, gave a short ignite talk at the most recent Museum Computer Network conference. The topic of his talk was how to “persuade your museum director to help you” (i.e. how to get him/her to invest in “innovation”). From the beginning of the video it’s easy to see one of the biggest, most glaring problems in our industry: He begins his talk by asking how many museum directors are at the conference. Very short awkward silence ensues…followed by laughter. Really?! Are even our conferences about innovation and new ideas attended primarily by middle managers?!

The reason for the lack of executive decision-makers at many conferences is not necessarily the fault of museum CEOs (as the conferences aren’t always adequately geared toward Directors). But it’s not wholly the task of middle managers to communicate and justify the imperative to remain relevant to CEOs either. There’s a messed up barrier to betterment here, and it has more to do with a flawed structure than simple lexicon within an antiquated museum hierarchy. His talk is absolutely true, probably staggeringly helpful, and thus amazingly messed up at the same time.

We’ve developed this detrimental idea that “digital” has to do with “tech” (not people), and “innovation” isn’t necessary for survival. Max Anderson’s “primer on the psychology of museum directors” underscores that the status quo (and, of course, legacy!) is what museum directors are primarily interested in…but the status quo isn’t working to bring in more people by creating crowds OR buzz. Efforts to abide the current condition fundamentally ignore the challenges imposed by a broken model. Changing lexicon is a pivot. Pivots sound pretty. Pivots sound agile. After pivoting, however, you may be facing in a different direction but you’re still standing in the same place.

Millennials – the largest generation in human history – may necessitate an update to the visitor-serving model in the information age. These “kids” will soon have kids, who will eventually have more kids, and if we continue to ignore the reality of negative substitution in our attendance, then we may soon have no museums, aquariums, or symphonies for those “kids” to go to at all. (OK – perhaps some hyperbole. We likely won’t have zero museums. Just more empty ones.)

The forces of change that propel the world forward are not going away. If we don’t change our model to one that is more sustainable, then we risk going away. This is a moment when our biggest barrier to engaging emerging audiences is holding dear to our increasingly irrelevant plans and practices. We need a reset. And it’s up to all of us to put our heads together and make it happen.