Bad things happen to good organizations when conference attendees leave their thinking caps at home.

Industry conferences can provide amazing opportunities for cultural organizations to learn about new initiatives – but there is a disease of sorts that can infect well-meaning leaders at these conferences, and they are bringing it back and infecting their organizations. It is time to talk about case study envy. That is the subject of this week’s Know Your Own Bone Fast Facts video!

I am a fan of conferences and those who know me personally (or have met me at one), know that I frequently lament how infrequently I can get to them due to my work schedule. On that note, let’s establish/acknowledge this important starting point: Industry conferences are important. We know this. I don’t and won’t dispute this because I believe it to be true. They provide important opportunities to learn about new ideas, celebrate achievements, discuss the state of the industry and obstacles for us all to take on together, and (perhaps most importantly) they connect us to one another as professionals and (when we’re lucky!) as friends.

Now that we have very purposefully acknowledged that conferences are generally awesome things for us, I am going to discuss an important way in which conferences are often NOT awesome. Are we ready? Okay:

Sometimes conferences make us stupid. And interestingly, data suggest that executive leaders know this. (More in a moment…)

There can be serious consequences for organizations that become too easily seduced by the alleged successes of others. I call this “Case Study Envy” and it takes place at all kinds of conferences. It does NOT mean that case studies aren’t important and that there isn’t value in sharing them. But just because industry conferences can be exciting does not mean that attendees should leave their thinking caps at home.

Case Study Envy can make smart people attending industry conferences believe two, pretty silly things:

1) That the organization or person speaking actually accomplished something.

Ouch. First, case study envy makes leaders believe that the presenting organization’s initiative worked and that it met any meaningful goals at all. Sometimes the initiatives are attached to meaningful outcomes and that’s great. But more often than not, the organization holding the microphone is someone who asked for the opportunity to tell you how good they are at something. This doesn’t necessarily mean that they are actually good at it. Considering this, it is not uncommon that programs and initiatives that might more objectively be considered failures are instead presented at conferences as successes. Let’s honest, it stinks to admit that something we thought was going to be cool, turned out to be a total dud. Sometimes, presenting that cool-sounding thing at a conference can internally soften the blow and save some public face.

When when you dig into 990s and look at them alongside presentations at conferences, it becomes clear that many institutions are actually sharing their failures as models of success. It certainly isn’t true for all organizations and presentations – but we often note at IMPACTS that if an initiative creates mission drift or costs a very large sum of money and has no demonstrative payoff, then it is going to be shared as a success at a conference.

The inclination to frame objective failures as successes makes perfect sense: There’s too much at stake to share our failures as actual failures. There are board member reputations, a CEO’s symbolic capital, and even funder satisfaction at risk when we admit to failure. If we admit our cool-sounding project was a failure, then we have to say to board members, “Hey, this big project that you supported and might have even been your idea didn’t work.” And we really don’t want to say that. So, instead, we say, “It didn’t increase visitation or notably impact our brand equities in a positive or even noteworthy manner, but it was something new and cool! To prove it, we’ll share it at [insert industry conference].”

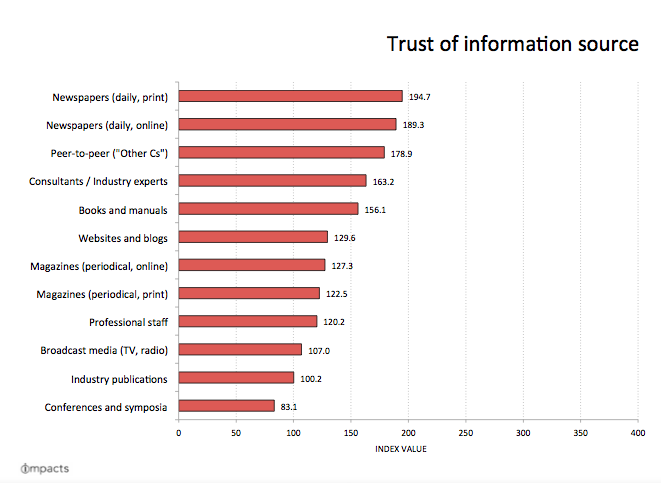

I am not saying it is an awesome situation, but the fear of calling a (very cool looking, sometimes high-tech) dog a dog may be understandable in this context that disproportionately punishes risk. What is more is that executive leaders seem to know that many of the case studies presented at conferences are actually failures – or at least, not worth influencing their decision making. It’s a reason for the inverse correlation between trust and influence and information being shared at a conference. Yes. Executive leaders find information shared at conferences to be less trustworthy because it is shared at a conference.

Here’s how much executive leaders trust various information channels. An index value less than 100 indicates lessened trust in the information based on its source. (Here is the link to the original post with the data and more information on it.)

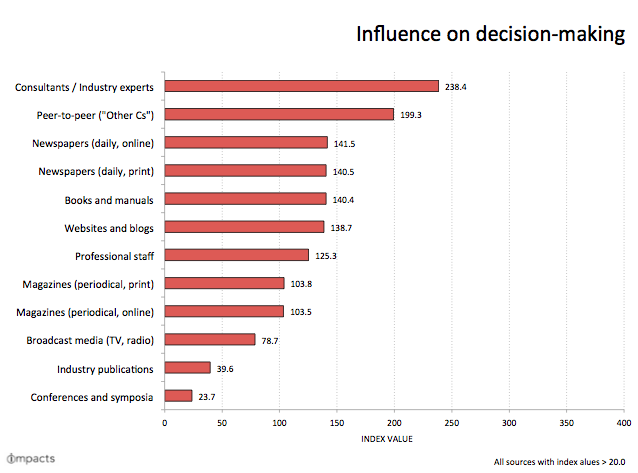

Think that’s bad? The data on the influence of information is much more alarming.

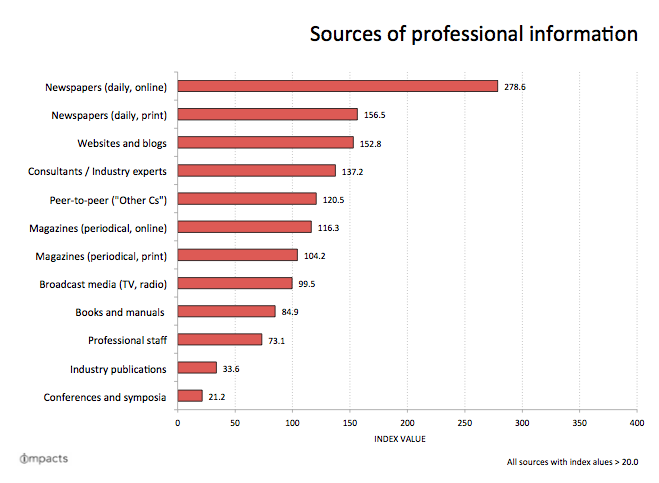

And on top of that, they aren’t exactly go-to sources of information, either.

Yikes! Again, this is not to say that all presentations at industry conferences are useless! Far from it! Conferences are a wonderful opportunity to connect and share experiences and, indeed, we need them. But they cannot help us unless we change how we approach them and stop making finding the things that actually work in increasing solvency or summoning support so difficult. We give the microphone to the folks that ask for the microphone (to talk about, say, membership) without much consideration for how well their (membership) programs actually work. Worst of all, there seems to be a particular want to give the microphone to some of the biggest organizations – and that can be dangerous if that particular organization is touting a failure as a success. It glamorizes the failure and promulgates it among the industry, resting its glory more on the symbolic capital of other aspects of the organization rather than that particular (futile) initiative.

There are many excellent examples of organizations of all shapes and sizes doing forward-facing things. It is a shame that those examples are sometimes diluted by glorious funeral ceremonies for futile projects disguised as successes at conferences.

So how can you determine the truly successful case studies from the hot air and combat Case Study Envy? Ask, “Did this initiative increase membership, result in more people coming through the door, or secure more donors? Did it contribute to meaningful and measurable market perceptions related to their mission?” Not every self-congratulatory program presented as a success is actually a success. Case Study Envy makes it hard to tell the difference.

2) That exactly what worked for that organization will work in exactly the same way for your organization

Case Study Envy causes infected leaders to make inappropriate comparisons between other organizations and their own. While case studies can be gold mines of valuable information, it is critical that leaders consider that organizations often have different assets and public perceptions. Among the industry, they tend not to be drastically different – but they are different enough that it may not be reasonable for one organization to expect the exact same initiative outcomes as another.

It is important for organizations to differentiate between models and examples. Both can be tremendously valuable…as long as we don’t mix them up. Many singularly successful organizations are terrible models because they have conditions that are not easily replicated (e.g. they have massive endowments, or a specific location in a specific city that supports their reputation, or they generally have a different funding model and business strategy). However, these organizations may still provide excellent examples for initiatives when elements of their success are identified and considered. Examples can aid in informing strategies and they often deal with the evolution of best practices or serve as case studies for engaging the market.

In sum, when at a conference, aim to evaluate the strategy driving the case study and if that may be helpful to your own organization. Attaching your organization to another organization’s specific tactics, however, can be tricky and may lead your organization to take on an initiative that simply was never strategically sound for you in the first place.

Many cultural organizations are doing remarkable things today. They are breaking boundaries, learning new lessons, and leading others! We need to keep these valuable lines of communication open and active. But just remember that there is often a lot of noise and it is our responsibility to our organizations to think critically about anything that can help make our organizations more successful and impactful.