Brain wave data suggest that when it comes to designing exhibits, it’s beneficial to start with the takeaway – not just end with it.

While exploring an exhibit, at what point in the experience are visitors most engaged? The answer to this question is the focus of today’s Fast Facts video. Brain wave activity data shows that traditional exhibit designers may have things backwards…

The video offers a smooth – and brief – walk through the information, so I encourage a watch. For my friends who would rather read the information, I’ve included detail below…

IMPACTS monitored the brain wave activity levels of 432 guests to special exhibits at three organizations using a wearable EEG device (a device that measures the electrical activity of the brain).

A brief introduction to wearable EEG…

This data is distinctly different than the market research that I traditionally share here on KYOB, so it’s worth an additional explanation. I talk quite a bit about thinking caps and, well, this contraption is a bit like a literal thinking cap.

The process uses a wearable electroencephalography (EEG) device. EEG is an electrophysiological monitoring method to record electrical activity of the brain. Hertz (Hz) are a measure of frequency – in this case, brain wave activity. Electrodes are placed along the scalp to measure voltage fluctuations resulting from ionic currents within the neurons of the brain, and measure the brain’s electrical activity over a period of time. Think of the outputs in response to the stimuli as a “bio measure” – an involuntary output that one cannot readily manufacture or control.

Our goal in doing this at IMPACTS is to measure brain activity in response to the stimuli present during a visit to the organization. Essentially, we aim to figure out when folks are most engaged during their visit.

If you are delightfully imagining with a dude wandering around a museum looking like Frankenstein, then you’re mistaken. (I know. I was bummed, too.) The EEG devices used by IMPACTS look a lot like baseball caps, and unknowing staff and other visitors are generally unable to tell that this person’s brain wave activity is being monitored.

Hz measurements generally correlate to states of brain activity. “Gamma” levels suggest hyperactivity in the brain, indicating high levels of engagement. “Beta” levels indicate more general engagement – much like taking part in a conversation – and alpha levels indicate a relaxed, near meditative state.

When are visitors most engaged in an exhibit?

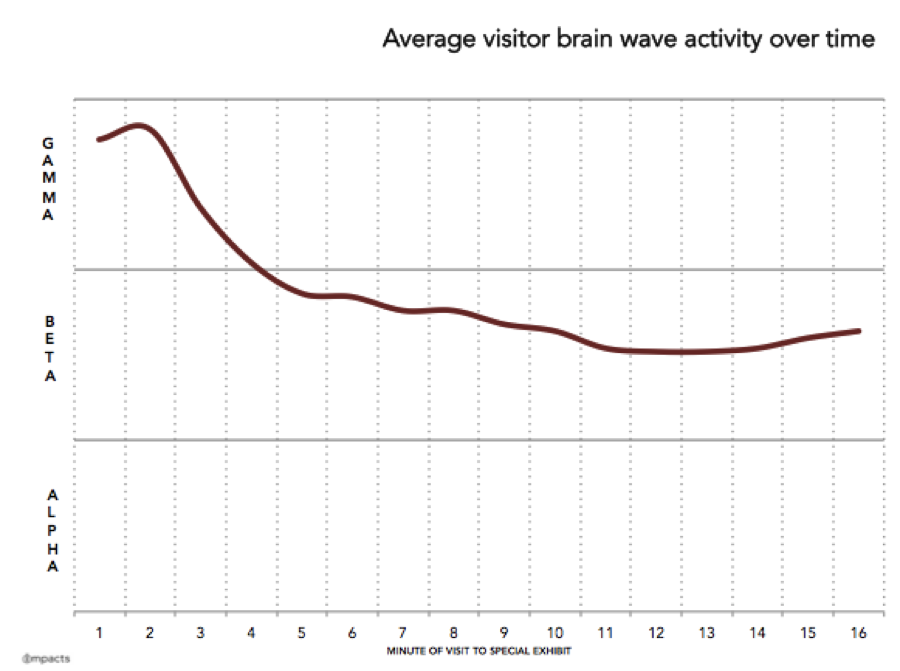

Let’s take a look at the average brain activity levels during the course of a stroll around an exhibit. The data comes from 432 guests at various exhibits within three, different organizations.

The average visitor engaged with the exhibit for 16 minutes. And, though the exhibits and the cultural entities were different, a clear trend in brain wave activity emerged…

Of course, engagement fluctuates – that’s not surprising. Though it may be a goal, it would be quite a feat to keep the average visitor at gamma levels during the entirety of their experience within an exhibit. (Hey! They can “alpha” with ice cream on the bench outside afterwards!)

The average visitor is most engaged at the onset of the exhibit, with measures suggesting Gamma-level brain activity (i.e. indicating high levels of engagement and stimulation). Brain activity measures then decline. After three minutes, brain activity levels decrease to Beta-levels. Brain activity remains at Beta-levels throughout the balance of the exhibit, on average.

This may not be surprising. External environments tend to change when entering a different exhibit space, when there’s the excitement of scoping out this new adventure upon which a person has embarked. It makes sense. What’s interesting is when we line this up with how some exhibits are actually structured – particularly those with a call to action (i.e. conserve, protect, be good to people, stand up for justice, don’t pollute, eat well, etc.).

This finding may challenge the “linear progression” notion of building toward a conclusion when designing an exhibit, because visitors are actually most engaged at the onset of the exhibit.

The takeaway: START with the takeaway

Traditionally, exhibits tend to be linear. They consist of the introduction of a topic, then gradually add detail and information, and then arrive at a key takeaway or conclusion at the end of the exhibit. The end is often where we hit our “so what?” The end is when we get to why the exhibit matters and, in some cases, the actions we want individuals to take to make the world a better place.

Some exhibits put the most important messages at the end of the experience, when folks are far less engaged than at the beginning of the experience. Of course, there may be no harm in placing these messages at the beginning and the end – but placing them at the end alone may miss an opportunity for impact.

Perhaps it’s time for exhibit design to move from the linear progression model to considering the integration of journalism’s well-established inverted pyramid. This model stresses starting with the most important takeaways, and then building a depth of supporting from there.

When we approach exhibits only as linear narratives – like bedtime stories – they are at greater risk of having the same results. When exhibits with key messages are structured more like news articles, they may have more resonance. This does not mean throwing out exhibit storytelling! This simply means making sure that if the exhibit has a critical takeaway, it is introduced at the beginning of the narrative experience when people are most engaged.

The height of engagement doesn’t happen at the end of an exhibit experience – it happens at the beginning. And while it’s a valuable aim to hold engagement over the course of the entire exhibit experience, data suggest that there may be value to making sure that what is most important is stated in the beginning.

After all, if there’s one thing that we want to say, don’t we want to say or introduce it when folks are most likely to listen?